Equities markets began 2019 battered by a very bad December and continuing concerns about the possibility of a recession because of weakening economic indicators and rising interest rates.

Should you and your clients be concerned?

“The extent to which what we’re witnessing is a mild economic slowdown or, as some are arguing, the start of a full-blown recession still is unclear,” Luc Vallée, chief strategist, economic research and strategy group, with Laurentian Bank Securities Inc. (LBS) in Montreal, states in a recent note.

LBS isn’t forecasting a recession, but Sébastien Lavoie, the firm’s chief economist, says LBS is very much aware of the many risks: escalation of the U.S./China trade war; a major downturn in equities; a lengthy shutdown of the U.S. government; closing of the U.S./Mexico border; pressure from U.S. President Donald Trump on U.S. Federal Reserve Board chairman Jerome Powell; increased turmoil in the Middle East; further buildup of North Korea’s nuclear arsenal; failure of the U.S. Congress to ratify the U.S./Mexico/Canada Agreement; and a difficult Brexit process.

However, Lavoie adds, the economies of the U.S. and, thus, Canada can continue to grow unless several risks materialize simultaneously.

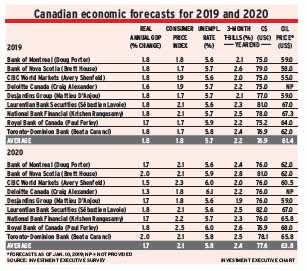

The other eight Canadian economists surveyed by Investment Executive (IE) agree. Their average growth forecast for real gross domestic product (GDP) growth for 2019 is 2.4% in the U.S. and 1.8% in Canada. The pace is expected to slow in 2020 to 1.8% in the U.S. and 1.7% in Canada. But that slowdown isn’t a recession – and isn’t alarming.

Both economies are operating at full capacity with relatively low unemployment and interest rates still at stimulative levels. In this environment, increases in interest rates are needed to make sure the economies don’t overheat. Nevertheless, central banks are becoming more cautious.

“The tone of the Fed has changed, implying less need to move rates higher,” says Paul Ferley, assistant chief economist with Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto. He attributes this to “the Fed’s perception of more headwinds in the form of trade protectionism, policy uncertainty now that the Democrats control Congress and financial market volatility.” Thus, Ferley anticipates the Fed’s overnight rate will rise to only 3% from the current 2.5%; previously, he had expected the rate to reach 4%.

For many of the economists, escalation of the U.S./China trade war is the biggest risk. If Trump goes ahead with additional tariffs on imports from China, a global recession would become more likely.

China’s economy already is showing signs of weakening due to the impact of high U.S. tariffs, despite China responding quickly with stimulative measures. But more tariffs would be very challenging – not just for China, but also for emerging countries that rely on trade with that nation and for resources exporters such as Canada, as oil and metal prices would be affected. Most economists currently assume that oil prices will recover to more than US$60 a barrel for West Texas intermediate oil from the low of US$46 at which they ended 2018.

Only one economist in IE’s survey – Craig Alexander, chief economist at Deloitte Canada in Toronto – foresees the trade war escalating, adding: “The odds are greater than 50% that there will be more U.S. protectionism this year and potentially more in 2020 as the U.S. presidential election nears.”

Alexander has the lowest real GDP growth forecasts for 2020: at 1.3% for Canada, and at 1%-1.5% for the U.S. But, he says, that isn’t because of the trade war, which won’t directly affect the U.S. economy significantly because exports are less than 10% of GDP. However, he does anticipate China’s growth will slow to not much more than 5% by 2020, vs the 6% or so the other economists predict.

What will pull down U.S. economic growth, Alexander says, is government restraint. In part, that’s inevitable as the stimulus from the 2018 tax cuts fades. But he anticipates additional restraint, given the huge U.S. public debt and federal deficits.

Avery Shenfeld, managing director and chief economist at CIBC World Markets Inc. in Toronto, also anticipates fiscal drag in the U.S. and forecasts only 1.5% growth for that economy in 2020, noting that some program spending is scheduled to end next year. With Congress in the hands of the Democrats, he’s assuming “inaction,” which will result in “modest tightening.”

Fiscal drag isn’t one of the risks currently worrying financial markets, but it’s an important one to keep in mind.

Another risk currently under the markets’ radar is high U.S. corporate debt. Lavoie points out that the debt of U.S. non-financial corporations now is more than US$15 trillion and that the quality of this debt has deteriorated, with more than half of the investment-grade debt rated only BBB.

The risk is that high premiums may be demanded on the large refinancings needed in the next few years for S&P 500 composite index-listed companies – about US$300 billion in 2019 and more than US$350 billion in each of the next three years.

There’s also the possibility of a mistake by central banks. Ferley understands why the Fed is cautious, but he’s a little worried that if rates aren’t high enough, inflation could take off. Wages are beginning to rise in the U.S. and could quickly feed through to higher prices on consumer goods and services. He’s forecasting 2.4% inflation in the U.S. in 2020.

Overhanging these expectations are the markets themselves. If investors continue to fear recession and sell, producing a plunge in valuations, consumer and business confidence could erode, says Alexander.