Canadians who establish registered education savings plans (RESPs) for their children are setting their kids up for financial success later in life because there’s a direct correlation between having post-secondary education and wealth, according to recent research from Mississauga, Ont.-based Credo Consulting Inc.

The research comes from the Financial Comfort Zone Study, an ongoing national consumer survey that Credo conducts in partnership with Montreal-based TC Media’s investment group. (TC Media publishes Investment Executive.)

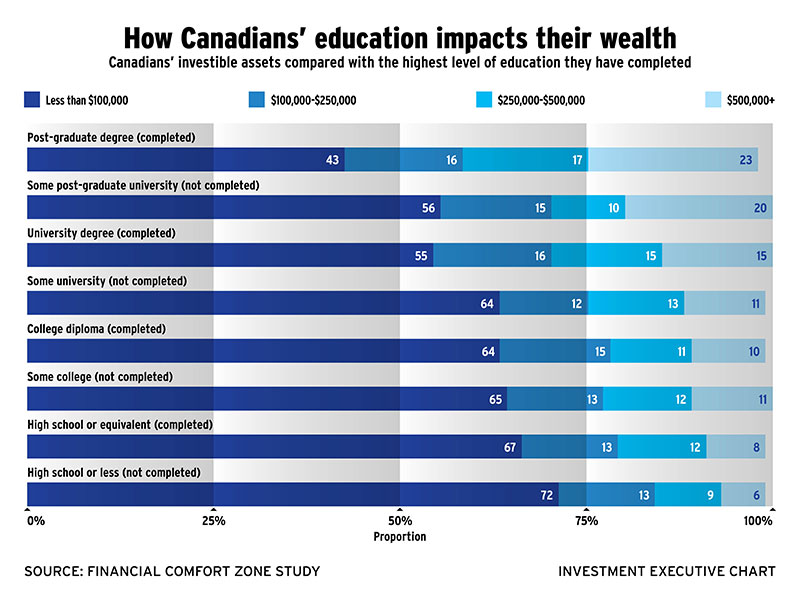

Among the Canadians Credo surveyed whose highest education level is a postgraduate degree, 23% have investible assets of $500,000 or more while 43% have investible assets of $100,000 or less. Among survey participants whose highest education level is a post-secondary degree, 11% have investible assets of $500,000 or more while 64% have investible assets of $100,000 or less. Only 8% of survey participants whose highest education level was a high-school diploma have investible assets of $500,000 or more and 72% have investible assets of $100,000 or less.

However, Credo’s research found that not enough parents are taking advantage of the benefits associated with RESPs.

Credo asked Canadian parents who were surveyed to rate the importance they ascribed to education. Among parents who gave education a high rating of importance and who had one or more children living at home, 49% indicated they had established an RESP for their children. Similarly, 45% of parents who gave education a medium rating of importance and who had one or more children living at home indicated that they had established an RESP for their children.

In contrast, only 15% of parents who gave education a low rating in terms of importance and who had one or more children living at home had established an RESP for their children.

This relatively low rate in RESP adoption among parents with young children – particularly among those who ascribed a low level of importance to education – is an opportunity for financial advisors to impress upon their clients the importance of an education to a child’s financial well-being and the power of RESPs to help fund an education, says Hugh Murphy, managing director with Credo.

“Advisors who help their clients appreciate the real value of education – and the power of education to improve an individual’s lot in life – are positioning themselves apart from advisors who don’t help on this front,” Murphy says.

RESPs are registered accounts that allow individuals – typically, parents – to save money for their children’s education. Contributions to an RESP are not tax-deductible, but all earnings realized in the plan accumulate tax-free until withdrawn. The federal government also provides a grant in the amount of 20% of annual contributions per child, to a maximum of $500 a year and $7,200 per child over the life of the plan.

When monies from the plan are withdrawn, the contribution amounts are tax-free, while earnings and grant amounts are included in the child’s income so long as he or she is attending an eligible post-secondary institution.

“[The RESP is] a fantastic investment vehicle,” says Himalaya Jain, wealth advisor and portfolio manager with ScotiaMcLeod Inc. in Toronto. “When you think about the grant component – that is, if you put in $2,500 for a child in a year, the government gives you $500 – that’s a 20% guaranteed rate of return.”

Young parents should contribute to a child’s RESP as soon as possible, says Kevin Dunphy, a financial planner affiliated with Investment Planning Counsel Inc. in St. John’s, N.L. Although RESP rules permit catch-up grants of up to $1,000 a year on contributions of $5,000 for parents who didn’t make contributions in previous years, establishing an RESP later in a child’s life will limit the potential compounded growth.

“Even parents of modest means should be able to put away $100 a month for their child’s post- secondary education,” Dunphy says. “Get the basic government grant, let [contributions and grants] grow at a reasonable rate of return over 18 years, and that should add up to $35,000-$40,000.”

Parents who are looking to secure the maximum RESP grant may be able to approach their own parents to see if they’re willing to contribute to grandchildren’s RESPs, says Sara Kinnear, director of tax and estate planning with Investors Group Inc. in Winnipeg.

However, having a parent rather than a grandparent establish and be the subscriber of the RESP is preferable, Kinnear says – especially in situations in which the child doesn’t end up attending a post-secondary institution. The rules governing the return of RESP contributions and income to a grandparent subscriber in those situations could result in unfavourable tax consequences.

“From a planning point of view,” Kinnear says, “I usually recommend that parents be the subscribers and the grandparents just give the parents the money.”