Business conditions in the retail investment industry have been quite rosy over the past year, but that isn’t stopping compliance officers (COs) and company executives from griping about regulation. Their dissatisfaction with the regulators that oversee their businesses is as strong as ever.

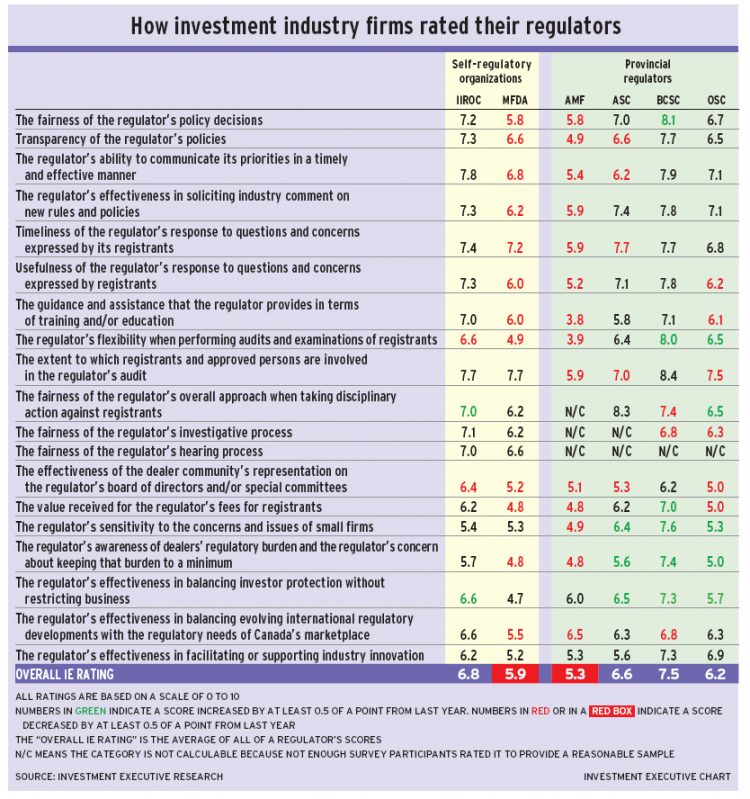

The latest edition of Investment Executive‘s (IE) annual Regulators’ Report Card revealed that survey participants’ opinion of most regulators was worse than a year ago. The exceptions to this trend were the B.C. Securities Commission’s (BCSC) overall IE rating (the average of all the regulator’s ratings), which ticked upward slightly to 7.5 from 7.3 in 2017, and the Ontario Securities Commission’s (OSC) overall IE rating, which remained at 6.2 year-over-year.

Meanwhile, the overall IE ratings for the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC), the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA), the Autorité des marchés financiers (AMF) and the Alberta Securities Commission (ASC) all declined year-over-year. In the AMF’s case, the decline to 5.3 from 6.7 last year was particularly precipitous.

However, there are a couple of caveats to keep in mind. First, ratings in this Report Card can be volatile – particularly for smaller provincial regulators, such as the AMF, for which sample sizes are smaller. Second, these ratings reflect the views of only one constituency – the investment industry. Yet, regulators have obligations to a variety of stakeholders, including issuers, investors, the public and other policy-makers.

So, in this context, ratings reflect only the industry’s assessment of their regulators. That said, COs’ and company executives’ opinion of their regulators declined year-over-year in general. For the AMF in particular, its declines meant the regulator garnered the lowest overall IE rating in the survey.

In fact, the AMF’s ratings declined by more than half a point vs last year in 14 categories for which the regulator received a rating (not including its overall IE rating). Notably, COs and company executives expressed frustration about their dealings with the AMF on several fronts. For example, many survey participants complained that communication with the regulator is poor on everything from compliance audits to enforcement.

“There’s no talking to them,” says a company executive with an independent full-service dealer in Quebec. “And when you find somebody good [to deal with at the AMF], you know they’re not going to last.”

In addition, a compliance executive with an asset-management firm based in Ontario reported the AMF recently conducted a desk review on the firm, then billed the company for the audit: “They billed me and I didn’t even know what they did. It’s insane. I almost lost it when that invoice came in.”

In contrast to the AMF, the ratings for the other three provincial regulators in the survey were steady for the most part. Most notably, the BCSC remained the highest-rated regulator among both the provincial securities commissions and the self-regulatory organizations (SROs).

In particular, the BCSC’s ratings rose by half a point or more in six of the categories in which it was rated and declined by that same margin in only three categories.

Meanwhile, ratings for the OSC, the largest provincial regulator, rose by half a point or more in five categories but declined by half a point or more in six categories. However, the OSC received praise from survey participants in a new category added to this year’s Report Card: “the regulator’s effectiveness in facilitating or supporting industry innovation.”

Specifically, the OSC’s collaborative approach in encouraging new technology contributed to a belief that the regulator doesn’t stifle business or insist on putting new rules in place as investment firms explore novel products, services and business models. (See fintech story on page 16.)

In fact, some survey participants would like to see the OSC take a bigger leadership role within the regulatory landscape.

“I would throw more power under the OSC,” says a compliance executive at a large investment dealer in Ontario. “I’d also expand the interaction among the OSC and the [other] provincial regulators in order to have a more co-ordinated national effort and leverage the OSC’s expertise in protecting consumers.”

The desire among survey participants for further regulatory consolidation also was evident when it comes to the SROs. In fact, several COs and company executives at investment dealers and mutual fund dealers alike said they would like to see IIROC and the MFDA merge.

Merger talk aside, the ratings for both IIROC and the MFDA declined year-over-year. But while IIROC’s overall IE rating dropped modestly to 6.8 from 7.0 year-over-year, the MFDA’s overall IE rating declined significantly to 5.9 from 6.5. Notably, the MFDA received lower ratings of half a point or more in 12 categories.

The MFDA’s rating in “the regulator’s flexibility when performing audits and examinations of registrants” suffered the biggest drop, declining to 4.9 from 6.6 year-over-year. Many COs’ and company executives’ criticisms of the MFDA’s flexibility in the auditing process involved both the details of audits and their timing.

For example, some survey participants complained that they’re repeatedly audited during RRSP season, while others said they’ve been inundated with simultaneous audits by multiple regulators, including the MFDA. This leaves these dealer firms’ COs and company executives frustrated with the regulators’ lack of understanding about the burden this represents for their firms.

Furthermore, several survey participants pointed to the importance of regulators having strong frontline personnel: the fondest wish of many of those surveyed is for regulators to hire staff with more industry experience.

“The [MFDA] hires lots of people with very little experience in the investment industry,” says a CO with a mutual fund dealer in Ontario. “If [the SRO] had a bunch of people with 10 years experience, it would help so much.”