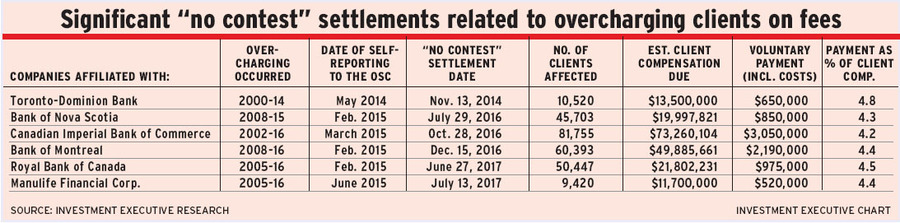

A series of settlements between regulators and firms affiliated with all of the Big Five banks reveals that hundreds of thousands of clients collectively were overcharged tens of millions of dollars. Ironically, financial advisors at one of the firms were among the first to uncover the issue, touching off reviews throughout the investment industry, which are ongoing.

The revelation of systematic overcharging among some of the industry’s biggest firms has all come to light through the Ontario Securities Commission’s (OSC) relatively new “no contest” settlement procedure, which allows firms to resolve enforcement cases without admitting liability.

In late June, Toronto-based Royal Bank of Canada was the last of the Big Five banks to settle such a case. Then, Toronto-based insurance giant Manulife Financial Corp. reached a similar settlement with the OSC in July.

Furthermore, Jeff Kehoe, director of enforcement with the OSC, indicates that the regulator still is working on several cases of similar overcharging issues.

Although the specific details of the various cases that the OSC has settled differ, there are some shared features. Essentially, firms were including products that contained embedded compensation within fee-based accounts, effectively charging clients twice.

In addition, some firms that offer the same product at different prices – i.e., mutual funds that charge lower fees for clients with larger amounts invested – weren’t necessarily putting all of their qualifying clients into the cheaper version of the product, thereby charging clients more than they should have been charged.

So far, the cases with the Big Five banks’ affiliates and Manulife indicate that more than 250,000 clients combined have been affected by these forms of overcharging. The settlements with the OSC have resulted in more than $190 million being returned to investors collectively, plus another $8.2 million in voluntary payments and costs to the regulator.

Although the OSC indicates that there may still more cases to come, the full scope of client overcharging in the Canadian investment industry may never be known.

Indeed, overcharging may not be clearly against the rules. Each of the regulatory settlements to date have identified the conduct being addressed in the enforcement action to be deficiencies in the firms’ internal controls that failed to detect the overcharging – not the overcharging per se.

Arguably, overcharging clients could be deemed a violation under securities law if the practice was found to be unfair, improper or fraudulent. The type of overcharging that’s covered in these no-contest settlements to date does not amount to fraudulent or improper conduct, Kehoe says, given that it was primarily the result of inadequate systems rather than deliberately dishonest conduct. However, the overcharging could be considered unfair to the clients involved, which would fall under the regulator’s “public interest” mandate.

There is no precedent for overcharging being treated as a violation of securities rules in Canada. In fact, a report that the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) published earlier this year, which details the results of a review of compensation-related conflicts at investment dealers, indicates that some firms allow assets that include embedded compensation to be utilized in fee-based accounts and simply address the conflict through disclosure.

Most investment dealers try to exclude these assets from the account fee calculation, the IIROC report notes. Yet, the report continues: “Findings from numerous business conduct exams provide evidence that these processes are generally manual and, as a result, are error-prone.”

This type of erroneous overcharging may be tricky to detect and is unlikely to generate full-scale enforcement action. In the OSC’s settlements with the bank-owned firms, the overcharging was limited to a handful of clients and a few thousand dollars, in some instances. In others, it affected thousands of clients over many years, resulting in millions of dollars of excess fees being paid.

Some of the bank-owned firms began discovering that they were overcharging clients – and had been for more than 10 years, in certain cases – as the firms began implementing processes to comply with the second phase of the client relationship model (CRM2) reporting requirements, says Elizabeth King, deputy director of the OSC’s compliance and registrant regulation branch.

The introduction of CRM2 prompted firms to begin examining what their required disclosure would look like under those rules, and that’s when they discovered the overcharging, she says.

However, sharp-eyed advisors also played a part in uncovering the issue, although they may have been concerned about possible undercharging instead.

According to the first of the no-contest settlements, reached with a trio of Toronto-Dominion Bank-owned firms in 2014, a division now known as TD Wealth Private Investment Advice found, “as a result of inquiries made by its investment advisors,” that certain clients were undercharged because products were being incorrectly excluded from their fee-based account calculations. At that point, the firm also realized that other clients were being overcharged.

These instances of incorrect charging arose at the big banks in particular, King suggests, as they acquired investment firms, thus adding to the complexity of their operations and numerous legacy systems had to be integrated. At the same time, fee-based accounts were becoming popular.

The widespread use of embedded compensation within various investment products, along with the increasing use of fee-based accounts, adds another layer of complexity that ultimately allowed the overcharging to continue at the banks over a prolonged period of time.

Another common feature of the overcharging cases that have been settled by the big firms is that they all involve proprietary products; none of the allegations of overcharging include third-party products.

Making the case that firms are unequivocally in a position to prevent overcharging that involves proprietary products is easier as the firms act as both the manufacturer and the distributor and have all the necessary information to identify – and prevent – any overcharging, King points out.

Still, there could be clients who are being overcharged either because their portfolios include a higher-fee version of a third-party mutual fund or because a third-party mutual fund that utilizes embedded compensation is being included improperly in fee-based accounts.

IIROC’s report on compensation-related conflicts indicates that the self-regulatory organization (SRO) will be paying close attention to these situations during future compliance reviews.

Paul Howard, director of communications and public affairs at IIROC, reports that the regulator wrote to dealers in April asking them to conduct internal reviews of their fee-based account programs to ensure that they have policies and procedures in place to detect and address these conflicts and, more important, that those policies are being followed. “That work is ongoing at the firms,” he says.

IIROC also will be looking for these conflicts in fee-based accounts during its compliance exams, Howard says: “[We can’t yet] provide an industrywide assessment of the results, but the compliance review findings on compensation-related conflicts will feed into IIROC’s normal oversight processes so that any issues are flagged and addressed appropriately by the firm and IIROC.”

IIROC’s report warns that if firms don’t self-report possible overcharging – and it’s later uncovered in a compliance exam – they are likely to be disciplined.

The Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA) also is looking for these overcharging issues during its routine compliance work with mutual fund dealers, says Karen McGuinness, senior vice president member regulation, compliance, with that SRO: “During our exams, we have been looking at fee-based programs and the premium/investor series issues [of mutual funds] with proprietary firms.”

The MFDA carried out a compliance sweep targeting fee-based programs in 2012 and has continued to review these programs, McGuinness adds: “We have seen a rise in new fee[-based] programs in the past couple of years, so [potential overcharging] is an area of increased focus for us.”

Although the SROs have yet to bring forth any enforcement cases of their own involving overcharging, the OSC states it has a few of these cases in the pipeline. However, these cases may be resolved via “no action” letters (NALs) rather than disciplinary activity.

“Now that we have our strong regulatory message out,” Kehoe says, the OSC is considering resolving certain other cases with NALs in cases in which the overcharging occurred on a much smaller scale and the firms in question self-reported the issue, have compensated affected investors and fixed the systems issues that allowed the overcharging to occur.

“Gone are the days when you can have a ‘one size fits all’ approach,” says Kehoe. Now, regulators are able to use “the right tool for the nature of the harm, and that’s leading to results that we haven’t seen in the past.”

Overall, including the settlements involving overcharging, the no-contest settlement program has been used to resolve nine cases, resulting in $340 million being returned to investors collectively. The program also has generated increased industry attention on compliance, Kehoe says: “I’m buoyed by that; it’s a clear example of the success of the program. We’re getting the change in behaviour.”

For firms that only now are discovering overcharging within their operations, Kehoe says, they still can get credit for co-operation if they come forward, then focus on remediation.

However, if a firm ignores these issues and they come to light a few years down the road, he warns, “my expectation is that we would hammer that firm from an enforcement perspective.”

© 2017 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.