This article appears in the June 2023 issue of Investment Executive. Subscribe to the print edition, read the digital edition or read the articles online.

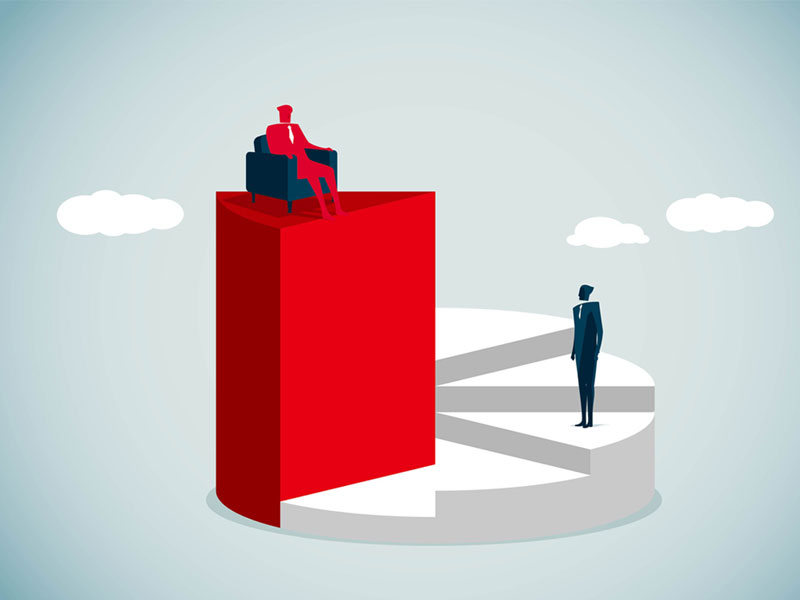

When investors lose money due to investment industry misconduct, their options for restitution are limited.

While the courts are slow and expensive, the Ombudsman for Banking Services and Investments (OBSI) is free but can’t enforce its recommendations for investor compensation.

Securities regulators can bring enforcement action and order penalties and disgorgement, but rarely manage to directly return money to harmed investors.

In an effort to do more for harmed investors, the Canadian Investment Regulatory Organization (CIRO) wants to pay the disgorgement money collected from sanctioned firms and advisors to the victims of misconduct.

The proposal, which went out for public consultation earlier this year, sounds simple enough. But some comments argued that the cost and complexity of administering a disgorgement distribution program may not be worth the effort.

“While the notion of directing funds earmarked as disgorgement to harmed investors has obvious appeal, we have some reservations about the need for and efficacy of such a program,” the Canadian Advocacy Council of CFA Societies Canada’s (CAC) submission stated.

For example, collection rates for enforcement sanctions have been relatively low, so a program to pay disgorgement proceeds probably won’t have much to return to harmed investors.

According to CIRO’s proposals, the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) collected slightly more than $1 million in disgorged funds in its entire operating history (from 2009 to the end of 2022), or less than 13% of the $7.9 million in disgorgement ordered over the period.

CIRO’s other predecessor, the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA), did slightly better, collecting 16% of all enforcement sanctions since it began ordering discipline in 2004. (While the MFDA included disgorgement in its sanction orders, the amounts weren’t separated from penalties).

Moreover, the disgorgement ordered in an enforcement case is likely to be much less than the loss suffered by a harmed investor. While CIRO could order a rogue financial advisor to repay their ill-gotten fees or commissions, an investor’s loss caused by misconduct — through a failed, unsuitable trading strategy, for example — could be many multiples of that amount.

Submissions also discussed the administrative costs to run a program that would involve vetting potential claims, applying a methodology to calculate each eligible claimant’s share of the disgorgement, and then paying those claims.

CIRO proposed tapping its restricted fund — which holds the money paid in enforcement sanctions — to cover these expenses. However, investor advocates argued the administrative costs should come out of CIRO’s operating budget, which would maintain the restricted fund for its intended purpose of educating and supporting investors.

Advocis’ submission stated that using the SRO’s operating budget for these costs would lead to higher fees on firms and “significantly increase the regulatory burden.”

Amid these concerns, the CAC questioned whether the proposed disgorgement program would complicate harmed investors’ efforts to recover money through other mechanisms, such as OBSI, the courts or firms’ voluntary investor compensation efforts.

Absent improved collection rates and bigger disgorgement orders, “it is unclear to us whether the costs of implementing this proposal will create any meaningful incremental benefits for aggrieved investors,” the CAC stated.

Other investor advocates were generally in favour of any regulatory effort to help harmed investors recoup losses.

FAIR Canada’s comment letter stated that the benefit of returning money to victims outweighs the potential costs and complications.

“Various factors already restrict investors’ ability to obtain compensation,” FAIR Canada said. “These include litigation costs, limited resources for regulators to prosecute all cases involving loss, and assets that wrongdoers have hidden offshore. Given these realities, all possible avenues, including the program, should be available to help harmed investors recover their losses.”

The group also called on CIRO to improve the program by increasing its sanctions-collection rate by seeking additional powers from governments to boost recoveries from disciplined advisors. For example, FAIR Canada suggested that CIRO consider obtaining powers introduced in British Columbia to prevent people with unpaid regulatory sanctions from renewing their driver’s licence and licence plates.

FAIR Canada also argued that in cases where both a fine and disgorgement is ordered but only the fine is paid, CIRO should be able to use the money it collects to pay harmed investors.

Along the same lines, investor advocate Kenmar Associates suggested CIRO should prioritize collecting disgorgement over enforcing penalties so the potential recovery can be maximized for harmed investors.

Additionally, Kenmar argued disgorgement ordered by CIRO should cover the full amount of any ill-gotten gain, even though the wrongdoer may have retained only a portion of that money. For example, if an advisor generates fees and commissions from misconduct, the fraction of that revenue shared with the advisor’s dealer should also form part of the disgorgement order.

“These are dollar amounts resulting from an illegal act and therefore should not be retained by the dealer,” Kenmar stated.

A disgorgement success story

The Ontario Securities Commission’s (OSC) no-contest settlement program has enabled harmed investors to recoup hundreds of millions of dollars in excess fees and other overcharges from firms, although the mechanism has only been used in a handful of cases. The OSC’s credit-for-cooperation program also can consider the voluntary provision of investor compensation as a factor in setting sanctions, or even deciding whether to follow through with enforcement action.