The Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) has finally rendered verdicts on a pair of critical regulatory issues by deciding to scrap the idea of a “best interest” standard and declining to ban embedded commissions. However, along with these decisions, the group of provincial and territorial regulators has launched the next phase of reforms, which promise to remake the retail investment business.

The investment industry scored a major victory in late June, when the CSA announced its decisions on proposed best interest standards and embedded commissions. Industry trade groups opposed both measures, arguing that they would reduce investor access to advice.

However, the CSA aims to produce much the same effect – upgrading industry conduct and improving investor outcomes – through different means. And if the CSA follows through as planned on its proposed measures, the industry will be transformed fundamentally.

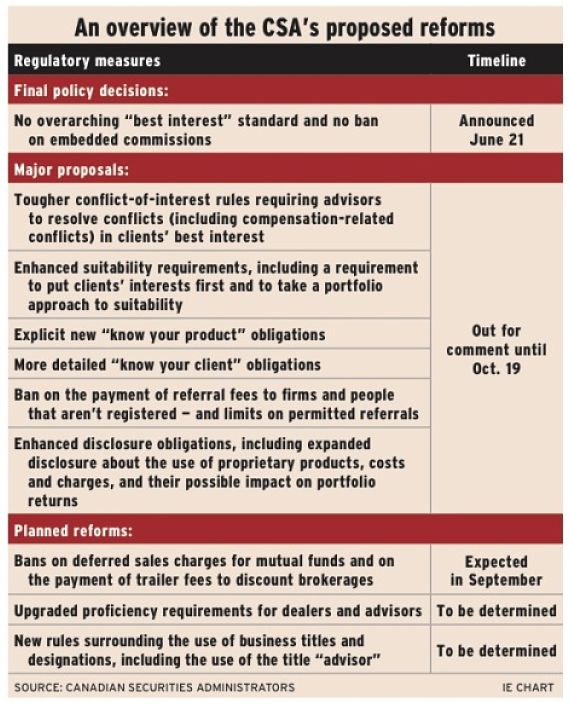

On June 21, the CSA unveiled a set of regulatory proposals that would usher in major changes to several long-standing regulatory staples, such as “know your client” (KYC) requirements, suitability obligations and conflict-of-interest rules.

Although the CSA will not be pursuing an overarching best interest standard, it seeks to incorporate best interest principles into many of the existing rules instead, thus requiring dealer firms and financial advisors to prioritize clients’ best interests nonetheless.

These initial proposals are now out for a 120-day comment period, ending Oct. 19. Yet, the industry already is sounding the alarm about how the proposed reforms could affect firms and advisors.

The Investment Industry Association of Canada (IIAC) warns that the CSA’s plans, if adopted, will raise compliance costs, drive shifts in product sales and alter business models. Ultimately, the IIAC warns, these changes could have a negative impact on advisors’ compensation and lead to further industry consolidation.

For the CSA, however, fundamental changes in the business are a feature of its proposals, not a side effect. The CSA is not aiming for marginal improvements; rather, it still hopes that the proposals will help correct the essential investor protection concerns that motivated this reform effort in the first place.

The CSA is concerned that information asymmetries and investors’ assumption that their advisors must act in their clients’ best interest means investors often rely too heavily on the industry, which leaves investors vulnerable to exploitation. The CSA remains concerned that existing conflict-of-interest rules are failing and that neither the industry nor the regulatory system is meeting investors’ expectations.

The seismic shifts the industry is warning about are just what the CSA is trying to achieve with these proposed reforms. Indeed, a regulatory impact analysis by the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC), which accompanies the CSA proposals, indicates that the reforms are expected to: produce client portfolios that are more diversified, lower in costs and likely to generate higher risk-adjusted returns in the long run; force the industry to re-evaluate its business models and practices; and enhance the ability of new entrants and smaller players in the industry to compete in the market.

For example, the CSA anticipates that the proposed changes to the suitability rules – including a requirement to prioritize clients’ interests when making investment decisions – when coupled with new “know your product” (KYP) requirements, will lead to better diversified, lower-cost portfolios.

Similarly, the CSA anticipates its proposed changes to the conflict-of-interest rules will have major impacts on the industry, too. The OSC’s analysis indicates that the proposed guidance regarding certain conflicts – such as use of proprietary products, the payment of third-party compensation and internal compensation arrangements and incentives – “will have a significant impact on the products recommended and distributed by registrants today.”

Overall, the OSC’s analysis predicts that firms that sell third-party products and proprietary products side-by-side will either have to enhance the competitiveness of their in-house products significantly or curtail their use. The analysis also foresees a shift toward index tracking and lower-cost products in general, as well as shifts in compensation structures (including an increase in direct-pay arrangements), greater use of products that don’t pay third-party compensation and a “movement toward internal incentive structures that better align with the interests of clients.”

The CSA fully anticipates that these changes will add costs for the industry. Indeed, the OSC’s analysis forecasts that the planned reforms will generate “significant one-time transition costs” as the industry adjusts to the new regulatory landscape. In addition, the analysis acknowledges that some of these costs are likely to be passed along to clients. But, ultimately, the OSC analysis concludes, the potential benefits will prove to be “more than proportionate” to the costs imposed.

Cost considerations aside, the fact the CSA is pursuing such sweeping changes is certain to prompt a good deal of resistance from the industry. The IIAC indicates it intends to propose alternatives to some of the proposals. In addition, the Investment Funds Institute of Canada (IFIC) set up a task force to review the CSA’s plans. That group includes three subcommittees to focus on specific aspects of the proposals – KYP, KYC and suitability, and conflicts of interest – to examine these subjects in detail.

None of the proposed changes are going to happen overnight. The CSA’s proposals are likely to undergo several rounds of consultation, comment and revision – not only at the CSA level, but also with the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC) and the Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA), which are going to be called on to incorporate many of the CSA’s proposals into their rules.

At this point, the timeline for these changes remains uncertain. Says Kristen Rose, manager, public affairs, with the OSC: “As with all regulatory reforms of this nature, it will take some time for changes to be fully implemented.”

The second phase of the client relationship model, which was the last major project that involved similarly contentious, fundamental rule changes, involved the CSA, IIROC and the MFDA. Finalizing the details of those rules took several years – and then several more years were needed to complete the implementation.

The CSA intends to introduce the proposed requirements in phases. Realistically, the final rules are several years away.

The CSA’s initial plan will give the industry two years to implement the core amendments to the KYC, suitability and conflict-of-interest rules once the details of those changes are final.

Moreover, the CSA has yet to propose formally the rule changes that will implement the planned approach to embedded commissions. At this point, the plan is to ban the payment of embedded commissions to discount brokerages and to outlaw the use of deferred sales charge (DSC) structures. The CSA states it will issue proposals on these policies in September.

The CSA’s goal with these anticipated proposals also is meaningful change. By doing away with DSCs and trailer fees for discount brokerages – along with the previously proposed reforms to suitability and conflict-of-interest rules – the CSA aims to eliminate some of the industry’s most egregious conflicts and investor protection failures.

Although the CSA isn’t proposing a ban on embedded commissions, the expectation is that these structures will become much less popular under the new rules. If these reforms don’t produce the changes the CSA is seeking, the option of an outright ban could be revived.

At this point, whether the industry will resist the ban on trailers for discount brokerages (an issue that’s currently the basis for proposed class-action lawsuits against a couple of bank-owned fund companies) is unclear, but the planned ban on DSCs will face industry opposition.

“While market trends will continue to reduce the prevalence of DSCs on product shelves and client accounts,” says Paul Bourque, president and CEO of IFIC, “we continue to believe that the DSC is a good payment option for some investors who would not otherwise have access to financial advice.”

Instead of an outright ban, Bourque says, IFIC will argue for enhanced guidance on the sale of DSC funds coupled with enforcement to stamp out any misconduct.