A decade ago this September, the global financial system was on the brink of collapse. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, policy-makers around the world rushed to fix fissures in the regulatory system that the crisis exposed. Much of that work now is done, and the financial services sector stands transformed as a result. The challenge ahead is to avoid complacency.

At the time, the global financial system appeared doomed as a host of the world’s largest banks teetered toward insolvency. In response, governments in the U.S. and Europe hurried to bail out most of them, while Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc., a U.S.-based financial services giant, was allowed to implode.

Although Canada’s financial system avoided the worst of the global financial crisis, our country certainly was not immune. At the height of the chaos, the federal government took action to prop up mortgage securities and the Bank of Canada deployed extraordinary monetary policy measures designed to keep financial markets liquid.

A total systemic failure was averted, but the turmoil touched off a worldwide recession and sparked an unprecedented global policy response as regulators and governments pursued reforms to shore up the financial system.

At the macro level, policy-makers sought to reinforce the resilience of the global banking system and to bring some oversight to the largely unregulated over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets.

In pursuit of these objectives, numerous, far-reaching reform efforts were launched. And while the fundamental requirements were agreed to at the global level, local regulators had to develop and implement the actual detailed rules. Given the scale and scope of the task, many reforms remain a work in progress.

The most urgent issues, such as the solvency of the global banking system, took priority. In those areas, major changes have been accomplished. Policy-makers have strengthened the financial system by toughening bank capital requirements and introducing leverage and liquidity limits – the Basel III requirements. The world’s biggest, most interconnected banks now must hold extra capital and submit to additional oversight. In addition, the initial reforms to enhance oversight of the global OTC derivatives markets – such as mandatory trade reporting and more central clearing – also are largely in place.

Yet, the effort to ensure big banks won’t be treated as “too big to fail” still is ongoing. The adoption of mechanisms to avoid future taxpayer bailouts by crafting regimes to “bail in” and resolve failing financial services institutions are not fully implemented. Similarly, measures to curb reliance on the so-called “shadow banking” industry are not high among policy-makers’ priorities.

Nevertheless, the reform efforts to date have altered the financial services sector fundamentally. The impact goes beyond the bottom line, as the crisis caused regulators to re-evaluate not just what financial services firms do, but how they do it.

Not only did the crisis expose weaknesses in the structure of the global financial system, it also shattered trust in the investment industry and exposed a wide array of individual and institutional misconduct. Thus, regulators around the world began considering reforms to the industry’s conduct standards in the wake of the crisis.

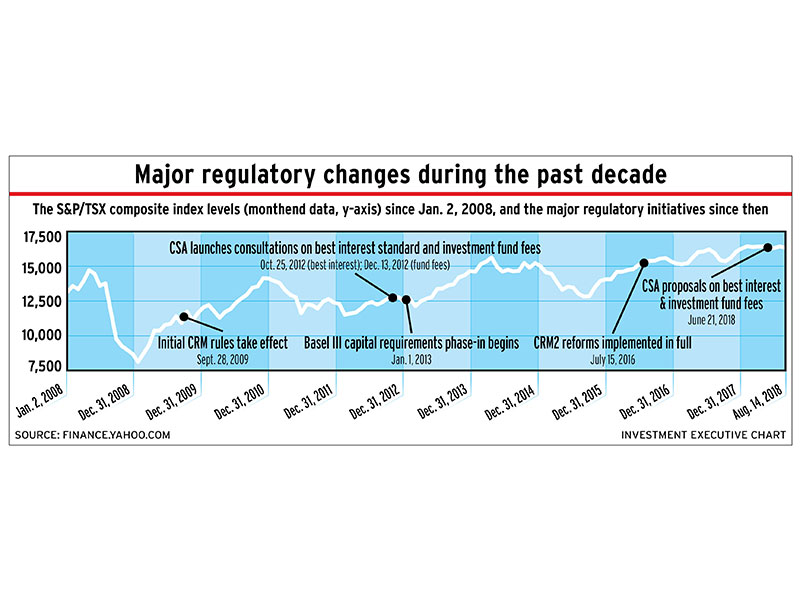

In Canada, fundamental concerns about how the industry treats its clients predate the global financial crisis. In 2004, the Ontario Securities Commission proposed a fair-dealing model to address concerns about how the industry operates. That initiative eventually evolved into the client-relationship model (CRM) reforms, which focused largely on enhanced disclosure.

Although the global financial crisis didn’t spark that initiative, the crisis validated regulators’ concerns and informed the ongoing policy development process. Thus, Canada’s regulators went ahead with reforms that required the industry to provide investors with more extensive disclosure, particularly regarding the costs of investing and portfolio performance.

At the same time, the crisis caused regulators around the world to question whether the traditional model of relying on disclosure could provide adequate investor protection. Post-mortems on the crisis, such as U.S. Congressional hearings, and criminal and regulatory enforcement cases focusing on industry conduct in the years leading up to the crisis, exposed an industry that often was predatory toward its own clients – even “sophisticated” institutional investors.

As a result, regulators began to consider whether the culture of greed pervading the industry should be addressed with stricter rules regarding conduct, compensation and conflicts of interest.

In the U.S., this produced parallel initiatives by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Department of Labor (DOL) to introduce new rules requiring broker-dealers to put clients’ interests before their own. The DOL rules remain in limbo amid industry-led legal challenges, while the SEC finally issued its own proposals earlier this year, which remain under consideration.

In Canada, the Canadian Securities Administrators (CSA) published a pair of papers in late 2012 raising the issue of whether dealers and financial advisors should be required to act in their clients’ best interests, along with whether reforms are needed in investment funds’ fee structures.

After years of research, consultation and study, the CSA proposed a series of “client-focused reforms” this past June that include measures to incorporate “best interest” requirements into existing securities rules regarding conflicts, suitability and “know your clients” and “know your product” obligations. Those proposals are out for comment until Oct. 19.

The CSA also indicated in June that it plans to ban deferred sales charge (DSC) mutual fund fee structures and prohibit the payment of trailer fees to discount brokerages amid concerns about a variety of negative effects that these mechanisms can have on investors – including worries that DSCs distort advice and reduce investors’ returns, and that disclosure often doesn’t work. The CSA is expected to issue proposals on these measures this month.

Both the CSA’s proposed client-focused reforms and its plans for mutual fund fee structures look certain to face intense industry pushback, as they are designed to alter how firms treat their clients fundamentally, which would also expand firms’ compliance obligations and are likely to affect the industry’s economics. If the process that produced the CRM2 reforms is any guide, several years are likely to elapse before these proposals are finalized – and adopting any changes will take even longer.

This is the first in a five-part series on the long-term impact the global financial crisis has had on the financial services sector