Raising a child will put a dent in most parental wallets, but that dent can turn quickly into a seemingly bottomless pit for parents who continue to support a child financially well into adulthood.

More and more financial advisors are dealing with older clients who are deferring long-anticipated goals – paying off debt, travel, dream retreats – to offer what may be the ultimate financial sacrifice, whether that is delayed retirement or reduced standards of living in retirement, because of the financial drain caused by adult children.

We’re not talking just about post-secondary education here; this extended parental support also includes resources for everything from smartphones, room and board, cars and the child’s first home away from the parents.

According to a recent study of affluent Canadians (those with $1 million or more in investible assets) by BMO Private Banking, a division of Toronto-based Bank of Montreal, more than a third (36%) of parents who responded worry about whether or not their child will be able to maintain a standard of living similar to their own after graduation. Most survey participants said they were not concerned about paying for their child’s education.

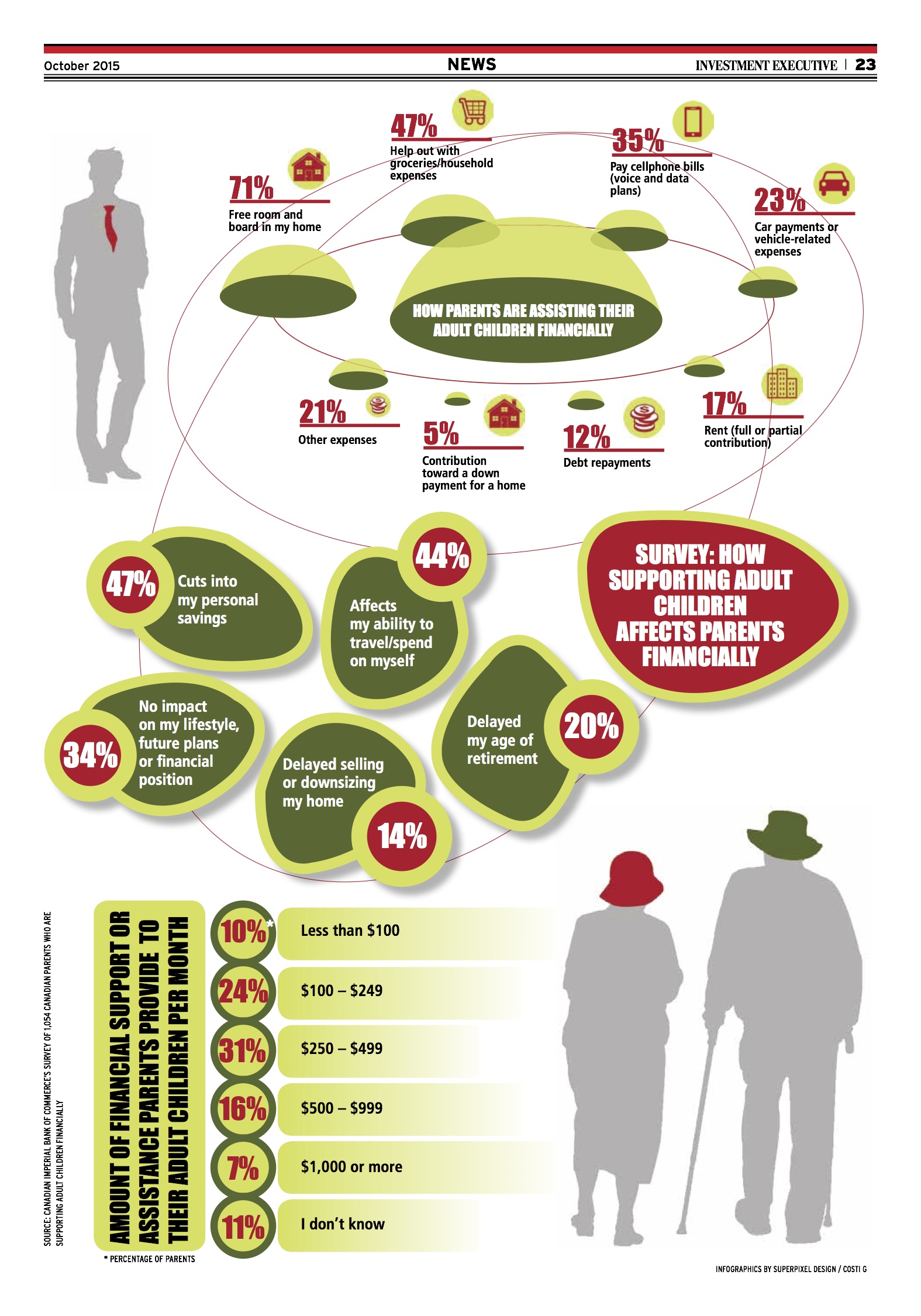

However, supporting a child financially after graduation is proving to be a strain for many Canadians. A recent study by Toronto-based Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC) found that 66% of parents have felt the financial impact of supporting their adult children. Forty-seven per cent of the parents surveyed by CIBC said that doing so has impeded their ability to save for themselves and another 20% said they have delayed their own retirement as a result.

Part of the issue is the rising cost of everything from tuition to cars and houses. Even the most industrious adult child is hard-pressed to meet these sharply rising expenses. For example, Paul Lermitte, senior wealth advisor with Assante Financial Management Ltd.’s legacy family office in Vancouver, had a car in university, thanks to some help from his parents, and was able to buy his first house when his in-laws came through with some extra cash.

However, Lermitte finds that trying to help his own children today is a much larger endeavour, as tuition and home prices increase.

“[The] education amount is bigger with my three sons,” says Lermitte, “helping them with cars is a bigger thing, helping them now get into a home is a bigger thing.”

Despite these rising costs, many Canadian parents willingly continue to funnel tens, sometimes hundreds, of thousands of dollars to adult children. According to the CIBC survey, 71% of survey participants said they provide their adult kids (non-students who are 18 or older) with free room and board, up from 32% in 1991.

The CIBC survey also found that about one in four parents spend more than $500 a month supporting their adult children and often foot the bill for their day-to-day expenses, whether it’s groceries and other household items (47%), cellphone bills (35%) or rent (17%).

You can keep your clients on track if they start planning – and educating – the whole family well in advance of a child’s 18th birthday. You can start by encouraging parents to talk to their children about money: methods can range from simple steps, such as counting coins being dropped into a piggy bank, and move on to more complex concepts as the child ages, such as sales taxes and the difference between needs and wants.

“Kids are interested in money,” says Laurie Stephenson, certified financial planner and owner of Starboard Wealth Planners in Halifax. “I think it’s something they should be learning about right out of the gate.”

You also can help your clients set up an allowance for their children to teach them about the importance of budgeting. For example, if a child wants a new smartphone, an allowance will show him or her how long it takes to save up for large purchases and how such goals can be delayed through miscellaneous spending, such as a frappuccino-a-day habit.

“If you teach that lesson early in life, it holds true for adults as well because, obviously, the wants are unlimited,” says Jamie Golombek, managing director of tax and estate planning with CIBC’s wealth advisory services division.

Besides a new smartphone, children can start saving for things such as spending money for a family vacation or, as they get older, their own education.

Although some clients may wish their child to put money in a registered education savings plan (RESP), children more commonly put money away in their own, separate account, Stephenson says.

Of course, you should be talking to your clients about opening and contributing to an RESP long before a child starts contributing to such savings.

Educating children about financial concepts is not just a job for parents. It’s also a great way for you to go that extra mile for your clients’ families.

Stephenson, Lermitte and BMO Private Banking offer seminars to clients’ (young) adult children or soon to be adult children. These workshops cover a range of topics, from general money management to buying a house for the first time.

Before buying that house, however, it’s likely that young adults will have to make some tough decisions about their personal budgets, both while in university and once they graduate. You may want to suggest that a client’s adult child consider what kind of phone he or she needs, says Lermitte. One with all the bells and whistles? Or would a basic talk-and-text phone be sufficient?

As well, does the child really need his or her own car, or is a shared vehicle or public transit a more viable option? Finally, young adults need to be honest with themselves about how often they can really afford to eat out or join friends at a bar.

Of course, clients need to get their own financial houses in order before they can expect their children to plan properly. Creating a budget with clients illustrates how much support they can afford to give to their children while also meeting their own financial goals.

Having that budget in place also comes in handy if a grown child starts taking up more and more of a client’s day-to-day budget.

“[Clients] can sort of lay down the law and say, ‘Look, this is how much we have as a family to spend and this is how much as a family we can afford to give you’,” Golombek says.

Indeed, children who are employed and living at home should contribute by paying rent rather than asking their parents for money, says Lermitte.

Clients can use the rent in two ways: to help out with the household’s daily expenditures or as a forced savings for the child’s financial future.

For example, parents could put the rent in a savings account that the child can use as a down payment on a house or to pay for other high-priced life milestones.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.