There are bulls and there are bears. And then there are true prophets of doom, such as the author of a new report that argues that economic growth is over and that Western society may be on its way back to a pre-industrial state.

This dark vision is sketched out by Tim Morgan, head of global research at London, England-based interdealer broker Tullett Prebon Group Ltd. The report – entitled Perfect Storm: Energy, Finance and the End of Growth – argues that our long run of economic growth essentially has come to an end, and the Western way of life faces collapse within the next 10 years: “If the analysis set out in this report is right, we are nearing the end of a period of more than 250 years in which growth has been ‘the assumed normal’.”

Although downturns, recessions and even an economic depression have occurred, it’s always been assumed that continued growth is the natural state of things. However, the report says: “That comfortable assumption is now in the process of being overturned.”

The report outlines a “lethal confluence” of four critical factors: the fallout from the biggest debt bubble in history; a disastrous experiment with globalization; the massaging of data that obscured economic trends; and, most important, the approach of an energy-returns “cliff.”

At the heart of this bleak view is the theory that the economy should be viewed in terms of its ability to extract and utilize energy, not in financial or monetary terms: “Money is the language rather than the substance of the real economy. Ultimately, the economy is – and always has been – a surplus energy equation, governed by the laws of thermodynamics, not those of the market.”

The report points out that the growth in both economic output and global population that has taken place since the Industrial Revolution is largely due to the ability to harness increasing quantities of energy: “Energy does far more than provide us with transport and warmth. In modern societies, manufacturing, services, minerals, food and even water are functions of the availability of energy.”

Now, that availability is in decline; thus, the prolonged period of growth must be in decline, too.

Morgan’s theory is reminiscent of the “peak oil” warnings, which suggest that the global supply of oil is deteriorating. However, the emphasis in Morgan’s report is not on the supply of oil itself; the report acknowledges that there are vast reserves of available energy, including Canada’s oilsands, shale oil and myriad other sources. The problem, the report argues, is that the cost of extracting energy from these sources is many times higher than it has been for extraction from the sources of easy, cheap oil that the have fuelled the global economy for so long.

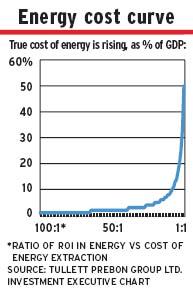

According to the report, the critical metric is the difference between energy extracted and energy consumed in the extraction process, a.k.a. “energy return on energy invested” (EROEI). The large oil discoveries in the early 20th century, for example, had an EROEI ratio of 100:1, the report says, because that oil was both abundant and easily accessed. However, global average EROEI ratios have been dropping for some time because existing reserves are depleted and new discoveries are smaller and tougher to get at, and thus are more energy-intensive to extract.

The report estimates that the global average EROEI ratio had fallen to 40:1 by 1990, and to 17:1 by 2010. So far, that drop hasn’t proven particularly disruptive, and the global economy has seemingly chugged along undaunted.

However, the report argues, when the EROEI ratio drops below 15:1, a dramatic escalation in the cost of energy as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) will occur, creating a drop-off in the availability of surplus energy to drive economic growth. (See chart.)

The report foresees a decline in the EROEI ratio to 11:1 by 2020: “…at which point energy will be about 50% more expensive, in real terms, than it is today, a metric [that] will carry through directly into the cost of almost everything else – including food.”

The report explains that as the costs of energy extraction rise, the volume of energy that’s available for everything else falls, including necessities (food, health care, government), discretionary spending and investment: “The essentials may still be affordable, but … energy available for discretionary uses diminishes rapidly. If EROEI falls materially, our consumerist way of life is over.”

And if EROEI drops far enough, even the necessities could become impossible to provide.

“It is hardly too much to say,” the report warns, “that a declining EROEI could bomb societies back into the pre-industrial age.”

And if that point were to be reached, the report suggests, conflicts over access to scarce resources are likely to follow.

The report also argues that the so-called “developed” economies are particularly vulnerable because of the fundamental disconnection between consumption and production that has emerged in the West in recent years.

The report calls the move to outsource production to emerging economies a “self-inflicted disaster with few parallels in economic history.” Western countries have cut back their production but increased consumption, boosting corporate earnings in the short term and enriching a handful of executives. The result is a significant loss of skilled, well-paid jobs.

“Western consumers,” Morgan writes, “sold each other ever greater numbers of haircuts, ever greater quantities of fast food and ever more zero-sum financial services [while] depending more and more on imported goods and, critically, on the debts used to buy them.”

This growing reliance on debt would be worrisome enough on its own. The recent financial crisis revealed the extent to which U.S. and European households had become excessively indebted, and policy-makers in Canada continue to worry about the inexorable buildup of household debt here, too, which probably has been stoked by the move toward rock-bottom interest rates in response to the financial crisis, the subsequent recession and the prolonged, weak recovery.

But this increased reliance on debt is hardly the main threat, according to the report, which suggests that the buildup of debt is merely symptomatic of the sort of shortsighted thinking that has fuelled economic growth in recent years and helped to overcome the rising cost of energy.

The bursting of that debt bubble (which may be yet to come in Canada) has helped to overturn economic orthodoxies. And the continuing economic slump has exposed the inability of policy-makers to find ways to pull out of it. The usual tricks for boosting growth, from slashing interest rates to large spending efforts, may have prevented a deeper recession, but they haven’t produced any strong growth yet, says the report: “These tools have worked in the past, and the fact that this time they manifestly are not working should tell us that something profoundly different is going on.”

Moreover, the report argues, the peril is being masked by increasingly distorted economic data, which don’t give policy-makers or the public true measures of inflation, GDP growth or unemployment. Nor do governments properly account for their spending and debt, the report says. But, these issues are really a sideshow to the main thrust of the report, which is the looming threat of massively higher energy costs.

One counter to this dark vision is that alternative energy and technology will restore the EROEI ratio to more comfortable levels. But the report is not optimistic on that count, either: “The magic bullet, of course, would be the discovery of a new source of energy [that] can reverse the winding-down of the critical energy-returns equation. Some pin their faith in nuclear fusion, but this, even if it works, lies decades in the future – that is, long after the global EROEI has fallen below levels [that] will support society as we know it.”

Other fledgling alternatives, Morgan’s report adds, such as biofuels and other unconventional hydrocarbons, aren’t the answer, either, because of their intrinsically low EROEI ratios. Biofuels and oilsands have an EROEI of about 3:1; shale gas has a return of about 5:1. The report is more positive about offshore wind, which boasts a claimed EROEI of about 17:1; but cautions that the process relies on some optimistic assumptions, and generates electricity, not fuel.

“In the absence of such a breakthrough,” the report concludes, “really promising energy sources (such as concentrated solar power) need to be pursued together, above all, with social, political and cultural adaptation to ‘life after growth’.”

© 2013 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.