The landscape for investment and insurance products has evolved significantly during the past decade. That’s because asset-management firms and insurers had to adapt to several changes, including new regulations and business models, and a shift in client needs.

Although themes such as increasing regulation or growing interest in ETFs already were in play in 2008, the global financial crisis – along with advancements in technology – helped to accelerate the changes in these areas.

“[The financial crisis] sped up what was already happening,” says Kevin Gopaul, global head of ETFs at Toronto-based BMO Global Asset Management, which includes mutual fund arm BMO Investments Inc. and ETF sponsor BMO Asset Management Inc. “People don’t like surprises – and the financial crisis was, in many people’s eyes, a surprise.”

In addition, before the financial crisis hit, there was lack of awareness among investors about the specific assets held in their portfolios or how those portfolios were constructed, Gopaul says: “So, [all this] led to a drive [toward] more efficiency and more transparency in the way investments were constructed and in the way [financial advisors] were able to communicate with their clients.”

Technology also played a role in shaping the investment products space during the past 10 years. In fact, Andreas Park, associate professor of finance at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management and director of research at Rotman FinHub, says technology, not the financial crisis, was the main driver behind the evolution of investment products – particularly ETFs – during the past decade.

Technology enabled electronic trading and the launch of new wealth-management platforms, such as robo-advisors, Park says: “Technology, more than the financial crisis, led to the rise of ETFs.”

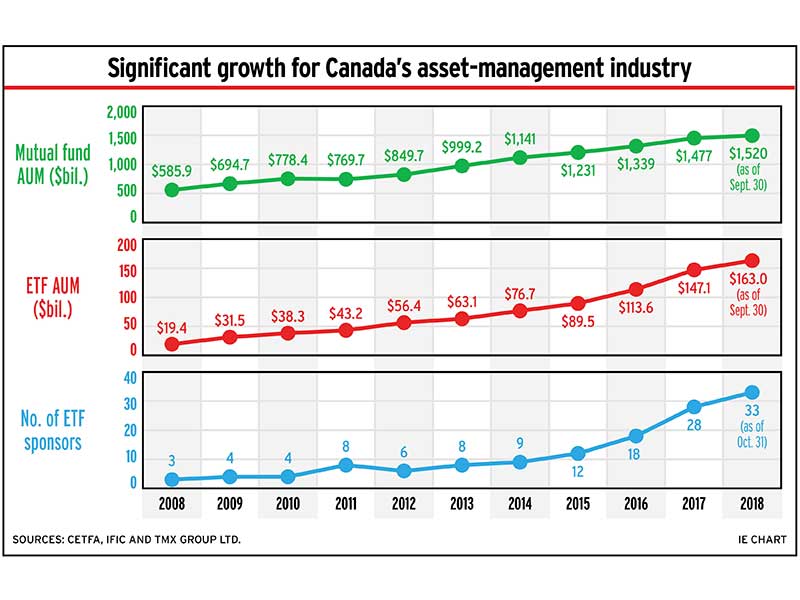

Although all financial products have undergone significant changes during the past 10 years, perhaps no product has become as prominent as ETFs. That is, ETFs as an asset class have expanded dramatically in virtually every measure since the global financial crisis. ETF assets under management (AUM) rose by a whopping 740% to $163 billion as of Sept. 30 vs only $19.4 billion at yearend 2008. As well, there were only three ETF providers in Canada 10 years ago, whereas there were 33 as of Oct. 31.

Change and innovation

“[There has] been a tremendous amount of change, and a tremendous amount of innovation [in ETFs],” says Gopaul. “And Canada has led the way, in many ways, of innovation happening globally [within this space].”

ETFs may have been the investment product story of the past decade, but mutual funds remain the dominant player. As of Sept. 30, mutual funds held $1.52 trillion in AUM, up by almost 160% from $585.9 billion at yearend 2008.

As the decade-long bull market buoys asset values and investors continue to put money into mutual funds and ETFs, what those investors pay for, and how they access, these products is changing.

New regulations, such as the introduction of the second phase of the client relationship model (CRM2), have put a spotlight on fees. New business models, such as fee-based practices and robo-advisors, also have added to the search for lower-cost products and ETFs, in general.

“We have seen an organic movement toward fee-based [compensation models] in the marketplace and, within that fee-based model, a movement toward low-cost products, efficient ways of gaining exposure to markets and ETFs,” says Tim Huver, head of product at Toronto-based Vanguard Investments Canada Inc.

In addition, how these products are packaged for retail clients also has changed during the past decade. For example, multi-asset products, such as balanced mutual funds, and products focused on specific outcomes or themes, such as responsible investing, have become more popular among advisors and clients.

“Investment outcomes are the new alpha; the new outperformance,” says Gopaul. “The notion of outperforming a certain benchmark will be less important.”

This shift in thinking surrounding portfolio construction has benefited ETFs as these products evolved into a key element in a portfolio rather than being treated as a novelty.

“ETFs have moved from [being] one of those products that were kind of interesting to have into one of those fundamental, core building blocks for many portfolios now,” says Pat Chiefalo, managing director and head of product for the iShares Canada division of Toronto-based BlackRock Asset Management Canada Ltd.

ETFs also have evolved in their very nature. Today, they’re a far cry from the passive, index- hugging products of a decade ago. Says Chiefalo: “The number and diversity of ETFs has absolutely exploded. If you look at the ETF market, pretty much everything you can think of under the sun is probably packaged up in an ETF.”

As of Sept. 30, there were 638 Canadian-listed ETFs available; these funds range from ones that follow broad market indices, such as the S&P/TSX 60 index, to actively managed funds focused on niche investment themes.

Since the financial crisis, active portfolio management has become more prominent in the construction of ETFs – in the form of factor-based (a.k.a. smart beta) ETFs, which are both passive and active in nature in that they replicate an index but also follow other criteria, such as value or momentum, in the hopes of boosting returns. There also are actively managed ETFs that don’t necessarily follow a specific index and are managed by portfolio managers.

In addition, the number of niche ETFs focused on a specific trend, such as blockchain or cannabis, rather than on a specific index have grown. In this way, ETFs are following in the footsteps of mutual funds, says Dan Hallett, vice president and principal of Oakville, Ont.-based HighView Financial Group: “In terms of the more niche products, the ETFs’ product segments picked up where mutual funds left off and took [the niche concept] to a whole new extreme.”

Low interest rates

Another major investment theme proliferating in recent years is that advisors are eager to find products to offset the low interest rates that have been the norm since the financial crisis. To that end, providers saw a growing interest in products that offer yield, whether through high-yield equities or high-yield bonds.

Besides investment products, the low interest-rate environment has led to some big changes in the insurance space. Insurance carriers have raised premiums and even removed some products, such as fixed annuities, from their shelves altogether. For example, Toronto-based Manulife Financial Corp. discontinued external sales of individual fixed annuities this past June.

Another area from which insurers have had to retreat recently is in the long-term care (LTC) market. Manulife and Lévis, Que.-based Desjardins Financial Security Life Assurance Co. (a.k.a. Desjardins Insurance) discontinued sales of their LTC insurance products in 2017 and 2018, respectively.

Nathalie Tremblay, health products manager, individual insurance, at Desjardins Insurance, points to slow sales rather than interest rates as the reason why these products were pulled from insurers’ shelves. In fact, this disinterest was a surprise to the insurance industry, given growth in both consumers’ interest in and sales for other living-benefits products, such as critical illness (CI) insurance.

“Companies entered into the market with long-term care [insurance] because it was the trend; it was [logical]. But we didn’t get the success we planned for,” Tremblay says. “In the best years, all the companies combined sold $10 million of long-term care.”

Meanwhile, CI products have gained considerable traction. In 2007, about $77 million in new CI insurance premiums were sold, says Tremblay; by 2017, that number had almost doubled to around $143 million. That last figure may be a drop in the bucket compared with the roughly $1.5 billion in life insurance sales in 2017, but, Tremblay argues, the growth in CI products marks a change in how advisors talk with clients about insurance in general.

“Traditionally, advisors concentrated on what happens if you die: if you plan to pay taxes upon death; if your family will be all right,” Tremblay says. “But advisors are beginning to say, ‘What if you get sick? Do you have income replacement? Do you have the financial flexibility to concentrate on the healing process?'”

Tremblay foresees continued interest in CI insurance even though life insurance still is light years ahead in terms of sales.

Similarly, investment funds providers anticipate continued growth for their products, whether ETFs or mutual funds.

In the case of ETFs, says Huver, there still is room for the product category to grow, even though there is likely to be some consolidation in this space.

“ETFs have been in Canada for more than 30 years, but, in many ways, still are in their infancy and many investors are gravitating toward ETFs for the first time,” says Huver. “So, [the outlook] still is very positive in terms of the foreseeable growth.”

However, mutual funds cannot be discounted regarding future growth and investor interest. Gopaul believes that although ETFs remain a good product, investors are likely to turn their attention once more to mutual funds because they can be more easily understood than ETFs.

Clients and advisors have to understand the mechanics of trading ETFs, particularly those focused on a niche market. Mutual funds could be more useful for advisors and clients who are looking to access a specific investment strategy without having to get into the nuts and bolts of the product.

Says Gopaul: “That’s where we’re looking to see some resurgence in mutual funds.”

This is the fourth in a five-part series on the long-term impact the global financial crisis has had on the financial services industry