Canada’s financial services sector has undergone a significant transformation in the decade since the global financial crisis of 2008-09, with the sector’s giants – primarily the big banks and insurers – swallowing up smaller shops, and independent firms merging among themselves at a steady clip.

What drives this trend toward consolidation, according to various observers, is the pressure on firms to evolve to meet changing client expectations, to invest in new technology and digital innovations and, perhaps most notably, to keep up with ever-increasing compliance costs.

“There’s no question that the 2008-09 disaster, mess, correction, really set the [stage] for what’s happening out there,” says Charlie Spiring, chairman and founder of Winnipeg-based Wellington-Altus Private Wealth Inc., which he launched in 2017 after selling his previous brokerage firm, Wellington West Holdings Inc., to National Bank of Canada in 2011. “[The crisis] brought about regulation – or overregulation, which is what I really believe is happening.”

For the Big Six banks, the acquisition of Canadian independent brokerages, mutual fund dealers and asset-management companies also represents an attempt to build scale quickly and accelerate growth strategies. These efforts have allowed the banks to take advantage of a bull market run that began in the spring of 2009 against the backdrop of a historically low interest rate environment, which tamped down revenue from the banks’ retail banking units.

“Wealth management represents a recurring revenue flow, so it’s of incredible interest to the banks – and it’s why you’ve seen tremendous consolidation,” says Walid Hejazi, associate professor of international business at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management.

Specifically, the bank-owned brokerage firms committed significant resources to their wealth advisory services and pulled the trigger on key acquisitions – both domestically and internationally – to add products and services as part of a continuing shift in focus toward serving the needs of the lucrative high-net worth (HNW) client segment.

For example, earlier this year, Bank of Nova Scotia acquired storied Montreal-based asset-management firm Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. – which caters not only to institutional clients, but also to HNW and ultra-HNW investors – for $980 million.

“[More than] 50% of people with a million dollars or more of investible assets are business owners,” says Glen Gowland, executive vice president of global wealth management for Scotiabank in Toronto. “If you look at the [overall] demographic shift, and all of those things relative to business succession, aging parents, etc., they’re here now. You need to build out the capability to retain and grow that important client base.”

Independent brokerages also have merged among themselves, looking to acquire scale to manage greater compliance and technology costs and to remain competitive vs the bank-owned brokerages.

For example, in 2009, Richardson Partners Financial Ltd. and GMP Capital Inc. merged to form Richardson GMP Ltd. Four years later, Richardson GMP bought out Macquarie Private Wealth Inc., the Canadian brokerage arm of Australia-based financial services giant Macquarie Group, which elected to retreat from the retail Canadian wealth-management space after acquiring Blackmont Capital Inc. from CI Financial Corp. in 2009.

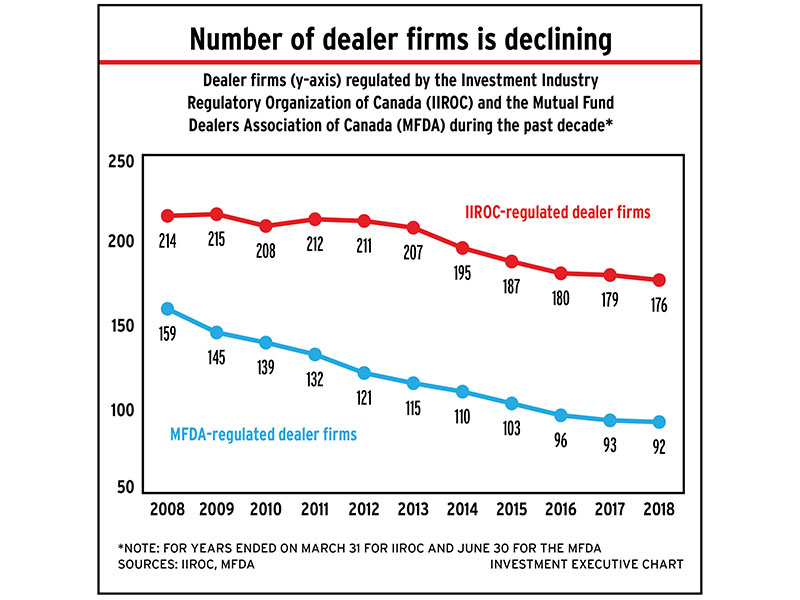

The various mergers and acquisitions over the past decade have resulted in fewer firms regulated by the Investment Industry Regulatory Organization of Canada (IIROC). In fact, the number of IIROC member dealer firms dropped to 176 as of March 31, 2018, from 214 in March 31, 2008. However, IIROC registrant numbers have been climbing steadily in recent years, to about 29,300 as of March 31, up from a low of 27,700 in March 31, 2009.

The mutual fund dealer channel also saw a significant degree of consolidation. Scotiabank acquired one of the largest names, DundeeWealth Inc., in 2010, renaming it HollisWealth Inc. in 2013. In 2016, Scotiabank sold off HollisWealth to Quebec City-based insurance giant Industrial Alliance Insurance and Financial Services Inc. (IA).

Consolidation also has thinned out the number of Mutual Fund Dealers Association of Canada (MFDA) member dealer firms to 92 as of June 30, 2018, from 159 in June 30, 2008, with the pace of decline tapering in recent years. But similar to the trend among IIROC-regulated registrants, MFDA-approved persons numbered about 80,500 in June, up from a low of 73,300 in June 2010.

“The smaller dealers were looking pretty vulnerable up until a couple of years ago, but in the past few years, there’s been a breath of fresh air,” says Chuck Grace, a lecturer at the University of Western Ontario’s Richard Ivey School of Business and managing partner and president at Bigger Picture Solutions Inc. in London, Ont.

That’s because client reaction to the enhanced disclosure introduced as part of the second phase of the client relationship model (CRM2) “wasn’t as big a deal as people feared,” Grace says, adding that innovations, such as providing advisors with access to robo-advice technology, have allowed firms to differentiate themselves.

The life insurance industry also has undergone significant change and consolidation during these years, with scores of small managing general agencies (MGAs) being acquired by the largest MGAs – the latter group being Woodbridge, Ont.-based Hub Financial Inc., Toronto-based PPI Management Inc., Kitchener, Ont.-based Financial Horizons Inc. and Mississauga, Ont.-based IDC Worldsource Insurance Network Inc.

The primary driver of that wave of consolidation, which began before the global financial crisis but has accelerated since, has been the search for scale, says Byren Innes, senior strategic advisor, financial services consulting and deals, with PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (PwC) in Toronto.

This increasing level of consolidation among MGAs has been all about “maximizing agreements with the insurance [carriers],” Innes says, “to offset some of the increased cost of operations to do compliance, the need [to pay] for increased technology, compliance staff, and basically more operational control. You need to get bigger to spend the money to stay in this business.”

Now, even the biggest MGAs are being acquired by the big insurers. Earlier this year, IA purchased PPI and Winnipeg-based Great-West Lifeco Inc. (GWL) acquired Financial Horizons last year, with both deals shaking up the industry.

“The MGA business has gone full circle,” says Jim Ruta, executive vice president of the Covenant Group in Toronto. “[Most MGAs] have become so large that they have managed to recreate the bureaucracies and the systems of the career companies they were formed to escape from.”

For the big insurers, one of the primary motivations for their acquisitions was the need to respond to coming regulatory changes, Innes says: “We know there will be more pressure on firms to provide oversight, supervision, compliance control and so on. How do I do that if I am four steps away from the actual advisor as a carrier?”

Acquiring MGAs also gives the big insurers an opportunity to secure shelf space for their products, Innes says: “If I own distribution, even if I don’t control distribution – there’s a big difference there, I think – at least I’m in a good position to be in a preferred position on the shelf.”

In the years to come, further consolidation in both the wealth-management and the life insurance industries can be expected, although the pace of those acquisitions may decrease.

“The banks will always look for acquisitions, but there are fewer and fewer targets remaining that they’d be interested in,” Grace says. “That’s why they’re turning their attention to places like Europe and South America. There are more choices [internationally] and not much left in Canada.”

In the life insurance business, many of the remaining smaller MGAs don’t represent ideal acquisition targets for the bigger MGAs, Innes suggests: “The attractive ones have gone already. You want to buy something that is half-decent in size so you [will] get something from it from a scale point of view or in number of advisors under contract.”

However, Ruta speculates, now that IA and GWL have acquired PPI and Financial Horizons, respectively, there will be “just a matter of time” before other big carriers pull the trigger on their own deals. “Big MGAs are going to be bought by the career companies,” he says.

Another continuing trend in both the wealth-management and life insurance industries is the emergence of digital advice and distribution platforms, such as robo-advisors. These platforms fill an increasing need in the mass- and emerging-affluent client segments, which still are underserved by the industry’s overall shift toward the HNW segment, experts suggest.

“[Robo-advice] is going to be a smaller piece of the industry – maybe 5% or 10%, which is not to be ignored because that’s [big] enough to matter – and it will target the smaller accounts in wealth management, which is fine because they need to be taken care of [because] banks are holding their noses up if you don’t have at least $250,000 [in investible assets],” Spiring says.

In the insurance industry, there will be continuing migration toward online or digital sales, although total share of business from those platforms remains low, says Matthew Lawrence, senior director in the financial services consulting group at PwC in Toronto: “More and more carriers will have some sort of digital direct offering if they don’t have it already. We know that there are potentially new entrants coming into that space [that will] leverage the fact that they now have a platform to target clients directly. We expect this trend will continue.”

Meanwhile, Spiring believes that there’s still great opportunity for independent players – such as his new firm – in the retail wealth-management marketplace, particularly if firms can leverage technology to stand out from the big banks, which he believes are held back somewhat by having to contend with legacy systems and processes.

Says Spiring: “The environment is ripe for success for someone with a good story and a ‘client first’ attitude.”

This is the second in a five-part series on the long-term impact the global financial crisis has had on the financial services sector