Canada’s retail investment industry has made a decisive break with its past in the decade since the global financial crisis of 2008-09. Namely, the industry isn’t a stock-picking and trading business anymore; rather, it has evolved into an advice-centred, relationship-driven industry. Up next, it must contend with the rise of robo-advisors – and the clients who love using them.

Already, the retail investment business looks much different from the way it did at the height of the financial crisis in 2008 – when trust in the global financial services sector imploded and yawning regulatory gaps were exposed. But the doom and gloom that surrounded the financial services sector back then failed to put much of a dent in the long-term health of the retail investment business.

To be sure, clients suffered some massive losses on paper alongside free-falling global stock markets and the subsequent, synchronized global recession. But for those clients who sat tight, those losses were erased relatively quickly and replaced by resurgent gains.

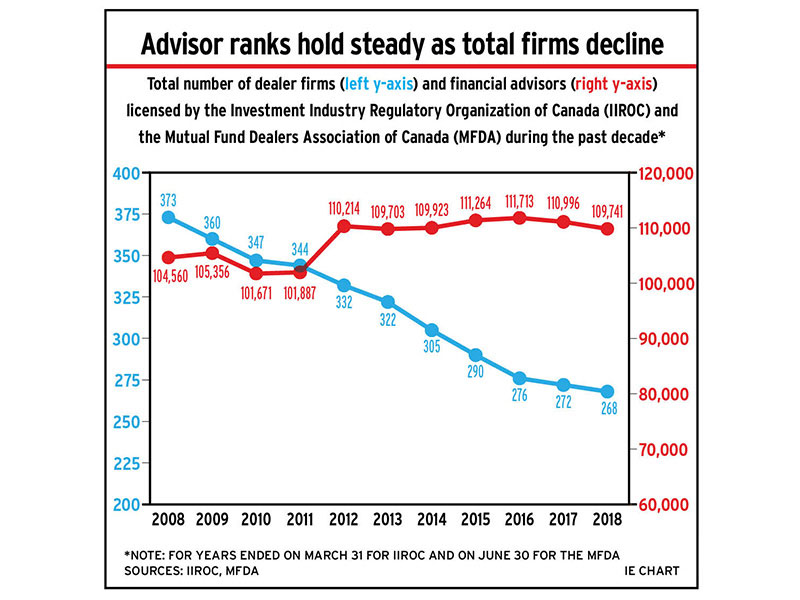

Canada’s retail investment industry also rode out the worst of the crisis largely intact. In fact, although there certainly has been some consolidation in the Canadian brokerage and mutual fund dealer channels during the past 10 years, the number of advisors at these firms has edged higher during that time.

In 2008, there were 214 investment dealers operating in Canada; today, that’s down to 176. Similarly, there were 159 mutual fund dealers back then; today, there are just 92. But the number of approved persons in the investment dealer channel has hardly changed during the past 10 years, remaining at about 29,300. Meanwhile, the population of mutual fund dealer reps has grown during the same period, to about 80,500 today from around 73,500 in 2008.

That the total number of advisors has grown in the wake of a seismic market collapse and the ensuing recession highlights the resilience of the demand for financial advice. This is reflected in the industry’s bottom line: operating profits for the large, integrated dealers have almost doubled during the past decade while profits rose by more than 60% for the independent retail firms, according to data from the Investment Industry Association of Canada.

Against this backdrop, the business of advice also is evolving. In general, advisors are running books of business that increasingly cater to higher net-worth (HNW) clients. The average advisor’s assets under management (AUM) has grown substantially during the past 10 years, but the number of client households that advisors serve has declined.

Specifically, advisors are serving fewer clients – and fewer clients with smaller accounts in particular. In addition, the compensation model has shifted significantly, with advisors relying much less on transaction-driven commissions and more on fee-based accounts.

Many of these macro trends are captured in the data Investment Executive (IE) collects each year as part of the annual Report Card series. For example, IE’s data show that average AUM across all four major industry channels – brokerages, mutual fund dealers, banks and insurance agencies – has risen to $82.5 million this year from $51.2 million in 2008. Yet, even as average AUM has grown by more than 60%, the number of client households being served across this much larger asset base has declined by almost 20% during this time – to 280.2 from 346.9.

This increasing focus on HNW clients also is evident in the account distribution data IE has collected for the Report Cards during the past 10 years. In fact, accounts worth less than $250,000 made up just slightly more than one-third (33.7%) of the average advisor’s book this year. But in 2008, these accounts represented almost half (48.2%) of the average advisor’s book. Conversely, accounts worth more than $1 million now make up 21.6% of the average book, up from just 14.1% in 2008.

This trend toward higher-value accounts reflects an ever- intensifying focus on serving wealthier investors – a trend that’s accompanied by a big shift in the industry’s revenue structure. Notably, the industry has moved away from an approach that rewards the volume of transactions and toward a system that gears dealers’ revenue and advisors’ compensation to AUM.

In 2008, the share of industry revenue derived from fee- and asset-based and transaction-based compensation was about equal, with each accounting for about one-third of overall revenue. (Across all four industry channels, 32.4% came from fees and 32.8% from transactions.)

Fast-forward to today and fee-/asset-based revenue is the dominant source of revenue, at 50.4%; in contrast, just 16% of revenue comes from transactions.

This shift is particularly evident among advisors at brokerages and mutual fund dealers. In fact, in 2008, advisors in the dealer channel reported that 45.8% of their revenue still came from transactions. This year, that figure was down to 17.5%, with the vast majority of revenue (78.7%) coming from fee-/asset-based sources. For advisors in the brokerage channel, the underlying trend is much the same, with commissions now accounting for just 25.8% of revenue, down from 45.8% in 2008, while slightly more than two-thirds (66.9%) of revenue now comes from fees and AUM, up from 43.7% in 2008.

These ongoing shifts are driven by several factors. For one, asset-based account structures arguably do a better job of aligning clients’ and advisors’ interests. If the value of a client’s portfolio grows, so does advisor/firm revenue. This compensation structure also blunts the incentive to trade frequently, which can undermine portfolio returns. From the industry’s perspective, fees are attractive as a stable revenue source vs transaction-driven revenue, which tends to be more volatile and sensitive to stock market activity.

At the same time, this shift in compensation structures reinforces the growing focus on wealthier investors. In the past, when commissions were the dominant source of advisors’ revenue, the total size of a portfolio was less important than the value of the transactions that an account generated.

So, a small, active client could be as profitable, or even more profitable, than a large client who trades infrequently. But as the value of transactions eroded, the importance of wealthier clients continues to increase – particularly among advisors at mutual fund dealers and brokerages.

At the banks – where advisors who ply their trade in the branches still are compensated on salary and bonuses for the most part – the necessity of targeting HNW investors isn’t as powerful.

At the same time, technology is enabling the creation of novel business models that can compete cost-effectively with the banks and traditional dealers for these smaller clients, who are steadily falling off the big investment firms’ radar.

The emergence of robo-advice enables smaller clients to access a new, stripped-down version of full-service advice. Robo-advisors mostly provide automated services, such as fundamental asset allocation, portfolio construction, dividend reinvestment and automatic rebalancing. Investors also can get some level of human advice from these services, a combination that creates a novel alternative to fit neatly between the traditional, high-cost, full-service advice model and the low-cost, no-advice, discount brokerage model.

At the same time, technology-driven innovation enables discount brokerages to push closer to the advice realm by providing their clients with access to increasingly powerful tools to help guide clients’ self-directed investing. Indeed, these advances in technology required regulators to reassess just what constitutes advice as they grapple with the increasingly fuzzy borders between traditional, full-service and do-it-yourself investing that are developing, thanks to the growing power and sophistication of technology.

Advances in areas such as machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) not only challenge the concept of advice; they also are changing its delivery capabilities. So, although technology has been an integral component of the financial services sector for many years, it appears that its influence is going to grow in the years ahead. Not only will technology augment the capabilities of robo-advisors; it’s likely to transform the traditional, full-service advice business as well as client expectations and demands evolve.

The millennial generation has grown up online for the most part and, as a result, these clients are much more comfortable than previous generations in transacting online. At the same time, millennial clients have much different expectations about access to service and advice, given the “always on, always available” online environment they’re accustomed to in other areas. These expectations are likely to help shape the face of advice in the years ahead.

For example, instead of periodic, in-depth meetings with an advisor, younger clients may expect much more frequent, but fleeting interactions online. These clients also may assume greater control of their investment decisions, given how easy monitoring an untethered portfolio and trading securities online are now.

As the delivery model for advice shifts in the years ahead, the advice itself also is likely to shift. As automation takes over more routine functions, such as collecting “know your client” information and producing basic asset-allocation recommendations, the value of human advisors will come increasingly from deep expertise in more complex matters such as tax and estate planning, which is so case-specific and technical that they will not be easy to automate.

There’s a long-standing question about whether the large technology companies that have come to dominate other aspects of modern life – such as Facebook Inc., Amazon.com Inc., Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc. (Google) – could venture into the financial services business, armed with mountains of customer data and AI-powered algorithms capable of guiding and triggering client action.

Whether or not future competition comes from these technology giants, technology is going to be at the heart of the future of the advisory business as client demands continue to evolve, fintech firms drive industry innovation and traditional firms adapt to survive.

This is the third in a five-part series on the long-term impact the global financial crisis has had on the financial services sector