Shadow banking was a major factor behind the 2008 global financial crisis and remains a threat to the world financial system, according to a recent report from Toronto-Dominion Bank.

The report, written by senior economist Francis Fong, notes that while regulators are aware of the problem, finding ways to prevent shadow banks from destabilizing the global financial system in the future has proved challenging.

“Shadow banking” generally refers to financial services intermediaries that do not take deposits and thus are not stabilized by deposit insurance or loans by central banks; this business model means shadow banks lack backup in the event of a liquidity crisis. These entities are designed to take advantage of regulatory gaps and avoid the associated costs; typically, loans are funded through deep, liquid pools, such as money market mutual funds.

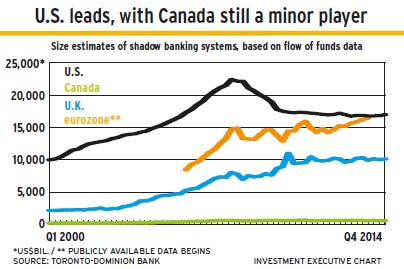

The size of the industry has declined since the credit crisis of 2008. However, shadow banks are growing again, especially in the U.S., the U.K. and Europe. Shadow banks are much less of a factor in the Canadian financial system, partly due to lower credit demand in Canada. In Canada, shadow banks are most active in mortgage lending.

Most regulators view the shadow banking system as a threat that is real, but not imminent. When loan demand is less volatile, traditional banks can supply much of the demand for loans.

But when loan demand surges, higher-risk borrowers go to shadow banks. U.S. demand was so strong for housing prior to 2008 that shadow banks provided much of the financing for subprime mortgages. These shadow banks then securitized those mortgages and sold them to traditional banks in the U.S., the U.K. and Europe.

Given how these high-risk loans eventually jeopardized the global banking system, better regulation of this industry clearly is needed. So far, however, tougher rules have been confined mainly to traditional banks, including increasing capital requirements and transparency.

Shadow banks are more difficult to regulate. Because they do not take deposits, they do not require deposit insurance or the emergency backing of central banks – the trade-offs that traditional banks make with regulators.

The biggest markets for loans made by shadow banks are in the U.S., with its pool of US$2.8 trillion in money market mutual funds. But these pools can be accessed by anyone, including U.K.- and Europe-based shadow banks, resulting in cross-border money flows that create a vast, interdependent market.

This situation leads to a number of risks. First, shadow banks lend to risky borrowers, who are likelier to default on their loans. Second, funding sources are all short-term, which means the shadow banks have to keep rolling over debt and could have difficulty doing so. Third, entities lending to shadow banks are taking on unrecognized risk. For example, money market funds are considered very low-risk or even risk-free. But if a fund lends to shadow banks and the loans can’t be repaid, the retail and institutional investors who invested in the fund will have losses.

Due to the low demand for credit globally, regulators still have time to develop regulations to lower these risks.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.