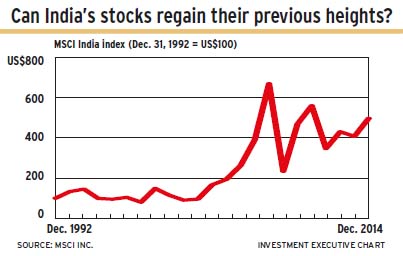

Several macroeconomic factors have aligned perfectly to ensure that India’s leading stock market, one of the best-performing markets in the world in the past year, appears poised to continue growing strongly.

“The prospects for India’s stock market are very good, especially for the long-term investor,” says Mark Mobius, executive chairman of Toronto-based Franklin Templeton Investments Corp.‘s emerging-markets group in Singapore.

In 2014, India’s bellwether S&P BSE SENSEX index rose by 41.1%, vs 7% for the MSCI emerging markets index, 24.3% for the S&P 500 composite index and 12.3% for the S&P/TSX composite index. (All increases are stated in Canadian dollars.)

“We are optimistic about the performance of the SENSEX, with a general base-case target of 38,700 in two years compared with 29,000 today,” says David Kunselman, senior portfolio manager and chief compliance officer with Excel Funds Management Inc. in Mississauga, Ont.

A Jan. 8 strategy report from Bank of America Merrill Lynch (BAML) also is optimistic about India. That report projects that the SENSEX will rise by almost 20% this year and will almost double to 54,000 by 2018.

To allay fears that the SENSEX’s 2014 performance was not a one-time event, the BAML report states that when India’s stock market produced a return greater than 30% – as happened last year – the market provided a positive return in seven of the subsequent nine occasions, averaging 22%.

The BAML report also indicates that stock market performance in the second year of a new government in India has been positive in five of the past six occasions between 1991 and 2009, returning an average of 25.8%. And India’s first majority government in 30 years, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, took office in May 2014.

Although Chuck Bastyr, vice president, investment management, and portfolio manager with Mackenzie Investments in Toronto, sees opportunities in India, he believes that Indian stocks are “expensive,” given the run-up in the stock market.

“A lot of stocks have rallied in anticipation of growth in earnings,” adds Matthew Strauss, vice president of portfolio management, global strategist and portfolio manager with CI Investments Inc. in Toronto. “There’s an opportunity to get into the market even at these valuation levels.”

Strauss believes that earnings growth will contribute to stocks not appearing to be “exorbitantly expensive.” But, he cautions, “There’s not a lot of margin for error” when relying upon earnings growth to make investment decisions. “Even if companies do well in 2015, their earnings might not be enough to support valuations.”

Indian equities are trading at an average price/earnings ratio of 15.7, which is in line with the stock market’s 10-year average, but way below its 2008 high of almost 25. Kunselman anticipates that “corporate earnings will grow at a compound rate of approximately 17% per annum for the next five years, and equities markets will mirror the strong earnings growth.”

Although “the performance of [India’s] stock market has been influenced by foreign investors who hold 20% of the market,” says Mobius, “we are now seeing the local investor moving into equities.” He adds that the keys to the Indian stock market’s continued strength “will be earnings upticks backed by lower input costs as well as inflows into equities by locals and continued support by foreign investors.”

The strength of India’s equities market is underpinned by several macroeconomic factors. Rishikesh Patel, portfolio manager with LGM Investments, a division of Toronto-based BMO Asset Management Corp., in London, U.K., says India is benefiting from: massive government reforms; lower commodities prices, especially for oil, one of the country’s largest imports; rising corporate profitability; a growing middle class; and a demographic dividend characterized by a youthful population.

The government’s reform program proposes massive infrastructure development in areas such as roads and railways; improvements in the legal, tax and regulatory frameworks; greater mobility of capital; and increased foreign and private investment.

There has been “a change in investors’ mindset” resulting from Modi’s promise “to streamline everything, remove red tape and lessen the country’s bureaucracy,” says Bastyr, who adds that Modi believes he can replicate his performance as former chief minister of the state of Gujarat, when its gross domestic product (GDP) grew at an average of more than 10% a year for more than a decade.

The World Bank’s Global Economic Prospects report, released in January, forecasts India’s GDP growth at 6.2% in 2015, up from an estimated 5.5% last year. GDP growth will be fuelled by increasing consumption, higher infrastructure spending and greater manufacturing exports, Kunselman says, adding: “The government will also reduce subsidies, contributing to an improvement in its fiscal balance, while lower oil prices will result in a reduction in the current account deficit to possibly a current account surplus in 2015.”

Falling inflation, resulting from lower oil prices, will lead to lower food prices, providing more disposable income in the hands of consumers and lower interest rates, Kunselman adds. In fact, the Reserve Bank of India cut interest rates by 25 basis points (bps) in January to 7.75%, and another 75-bps cut may be on the horizon.

There are opportunities in sectors such as consumer goods, technology and pharmaceuticals; as well as in banks, financial services firms and infrastructure.

Banks are benefiting from an improving economy, lower loan losses and increasing net incomes, says Kunselman, who holds State Bank of India, ICICI Bank Ltd., HDFC Bank Ltd. and Yes Bank Ltd. in his portfolio.

Bastyr holds HDFC and Indiabulls Housing Finance Ltd., the latter of which he views as an “aggressive newcomer” to the financing space.

Patel also holds HDFC and Yes.

In infrastructure, Strauss holds Adani Ports Ltd., one of India’s largest multi-port operators; Larson and Toubro Ltd., India’s largest engineering and construction firm; and Shriram EPC Ltd., which provides engineering services.

Kunselman owns IRB Infrastructure Developers, which is involved in the construction of roads and highways.

Although India is set to do well, risks remain. Mobius says the biggest risk for India is that companies and the country itself expand too quickly and excessively.

As well, Strauss cautions that a tightening of global liquidity could lead to a reversal of the fund flows into India.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.