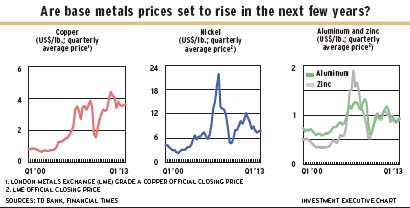

Although the shine has come off the prices of base metals, low-cost producers of copper, zinc, nickel and aluminum should still do well over the next few years and even better in the second half of the decade, when supply is expected to become tight again.

Much of the demand for these metals comes from China, which accounts for 40% or more of world consumption, but Scott Vali, a portfolio manager with Signature Global Advisors, a division of Toronto-based CI Financial Corp., believes the supply side is currently more important than demand.

Inventories are particularly high for aluminum because China has increased its production substantially and now is mostly self-sufficient. The result is that prices are profitable for only low-cost producers, which includes Canadian companies using cheap hydroelectricity, says Patricia Mohr, vice president and a commodities specialist with Bank of Nova Scotia‘s economics department in Toronto.

Nickel inventories also are high because China has developed a process to produce “nickel pig iron” from nickel/iron deposits. With that addition to supply, Mohr says, the current nickel price is not “particularly good.”

Zinc is in better shape, and its current excess inventories are expected to drop as some major mines close in Canada, Australia and Ireland. Mohr calls the current commodity price “quite profitable” and thinks zinc will be “extremely lucrative” by mid-2014.

Copper is just now moving into excess supply. Although this situation is expected to continue for a few years, demand is so strong that the risk of a major downward movement in price is unlikely. Mohr says copper production has been “extraordinarily” profitable.

Strong prices are important because profitability is being reduced by escalating costs, which have been rising by 5%-15% a year, says Onno Rutten, vice president, investment management, with Mackenzie Financial Corp. in Toronto. A major reason for this is rising energy costs, but wage increases have been just as important. That’s because most mining is done in remote areas and companies have had to offer high, rising paycheques to get the labour they need.

In fact, Rutten points to the $200,000-$300,000 paid to mine truck drivers in Western Australia and says wage increases generally have been 10%-20% a year. (All figures are in U.S. dollars [US$].)

In addition, the ore being mined is of a lower grade in many mines, especially for copper. Producers always start with the highest-grade ore and the easiest to access, Rutten also notes. Nevertheless, he adds, the price downside is limited in many base metals if global growth picks up as expected. Although many economists expect global growth to be only slightly above the 3.1% seen in 2012, they predict an acceleration to almost 4% in 2014.

One other factor that would affect demand for base metals is the US$, says Peter Buchanan, senior economist with CIBC World Markets Inc. in Toronto. If the US$ strengthens further, demand may weaken because the metals are priced in US$. However, Buchanan thinks the recent run-up in the US$ has run its course.

Here’s a look at the four base metals in more detail:

– Aluminum. Supply has been greatly increased by production in China and the Middle East.

Thus, strong increases in prices are unlikely in the next few years, but prices are expected to rise to about $1 a pound in 2014 from the recent 88¢/lb. as a result of production cutbacks.

Mohr believes China will have to import more aluminum around the middle part of the decade, so prospects are better in the longer term.

– Copper. This base metal is extremely important to the global economy because of its use in industrial production, electronics and construction.

A major source of demand is the expansion of China’s electricity grid, which uses about 40%-50% of the country’s copper consumption. Because the expansion of the grid is part of China’s five-year plan, Rutten says, the consumption is steady, so the price of copper is less sensitive to cyclical factors.

“All copper mines” are still making cash operating profits at the recent price of about $3.50/lb., Rutten says, noting that the break-even point for high-cost mines is around $3/lb.-$3.20/lb.

There’s a debate about how much supply will increase in the next few years. Mohr thinks supply may not rise as much as expected. Most will be “brownfield” projects – that is, expansion at existing mines. She notes that China has had some difficulty in boosting output, mainly due to the low quality of the grades of ore left in many mines.

Nevertheless, Mohr believes there will be some new supply and expects the price to drop to about $3.20/lb. in 2014 and a little lower in 2015 and 2016 before picking up in the second half of the decade as supply tightens substantially.

Rutten believes that supplies will become tight around 2015-16 because of the difficulty in finding good projects in good locations and the hesitation on the part of mining companies that are feeling the pressure to return capital to shareholders.

Vali can see the price dropping below $3/lb, but doesn’t believe a price that low would be sustained.

However, Buchanan is forecasting prices to rise to $4/lb. in 2014. He says copper demand will be supported by housing construction and automobile production in the U.S.

Besides stronger than expected demand, there could be mine disruptions – particularly in South America – that delay expansion or lower output, says Dina Ignjatovic, an economist with Toronto-Dominion Bank in Toronto, who forecasts a price of $3.60/lb. this year but just $3.34/lb. in 2014.

– nickel. The price of this metal has fallen to $7.50/lb. from $10.33/lb. in 2010, held back by uncertainty about the global economy and weak demand for stainless steel, which accounts for 60%-70% of consumption.

Mohr thinks there will be an uptick in demand this year that will strengthen in 2014, when she expects global growth of 3.8%.

China’s nickel pig iron production, which accounts for about 15%-20% of global output, is a factor holding prices down – and analysts expect that country to continue to increase its production of the substitute.

One potential problem is that Indonesia, from which China buys much of the iron/nickel ore used for the product, is threatening to ban exports of metal ores. However, Mohr says, there are other sources of the ore.

Mohr expects nickel’s price to stay low, averaging around $8.25 this year and next. She notes that the increased demand in 2014 will be offset by several major projects that are or about to come onstream. However, she sees the price picking up around the middle part of the decade.

Vali agrees that nickel could be interesting in the longer term because of the “inability of Western producers to find new supply.”

– zinc. Production is very fragmented, with thousands of mines, particularly in China, so it’s hard to estimate the output.

However, there are some big mines reaching the end of their productive lives, which should help lower inventories.

The marginal cost of production is 80¢/lb. to 90¢/lb., which means, says Rutten, marginal Chinese mines are barely breaking even at the recent price of 88¢/lb.

However, large mines, such as those belonging to Vancouver-based Teck Resources Inc., are still very profitable, given their costs of 40¢/lb.

Buchanan and Rutten are forecasting an average price of 95¢/lb. this year, but both Ignjatovic and Mohr expect it to be $1/lb., which, Mohr says, is “quite profitable.”

Rutten predicts $1.04/lb. in 2014 vs Ignjatovic’s $1.11/lb. and Mohr’ $1.15/lb. Mohr also sees the price rising to $1.40/lb. around the middle part of the decade.

© 2013 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.