The swoon in oil prices this year tends to be the focus of attention these days, but may not be the biggest economic challenge facing Canada in the next two years.

The biggest cloud hanging over Canada’s economic growth prospects may prove to be global economic volatility, according to eight economists from financial services firms surveyed by Investment Executive (IE).

“I can’t remember a time when there was so much uncertainty,” says Aron Gampel, vice president and deputy chief economist at Bank of Nova Scotia in Toronto.

The global economy is very soft, with the economies of many countries – not only China – weaker than expected this year.

Case in point: much uncertainty remains over the economic predicaments of Greece and other heavily indebted European countries, and a sudden surge of refugees into Europe also may affect overall economic prospects.

The economists whom IE surveyed anticipate that global economic growth will pick up in 2016, but financial markets have to be convinced the upturn is sustainable. Otherwise, the turmoil and volatility will continue and could postpone the long-awaited increase in interest rates by the U.S. Federal Reserve Board. (Such an increase would be the signal that economic recovery is entrenched.)

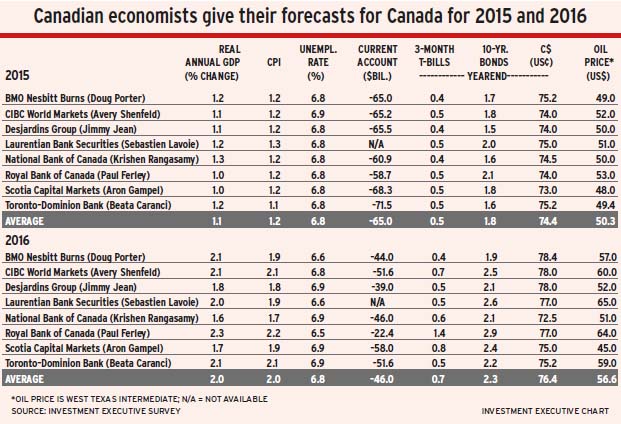

The eight economists surveyed forecast a 2% rise, on average, in real gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016, following this year’s 1.1%. That’s a good deal less than the 2.7% growth they foresee for the U.S. economy in 2016 – and they expect Canada to continue to lag the U.S. for a number of years thereafter.

Although there was an oil price-induced technical recession in Canada in the first two quarters of this year, economic growth has resumed. In fact, there has been remarkably little bleeding in Canada, a country in which oil production is a major sector. Part of the reason is that the drop in oil prices has benefits. Lower gasoline prices are giving consumers more money to spend on other goods and services, and non-oil businesses are seeing their energy costs fall as well.

The drop in the oil price also has reduced the value of the Canadian dollar (C$) against the U.S. dollar (US$). That makes Canada’s manufactured goods more competitive, both in the U.S. and at home against imports.

With oil priced in US$, the lower loonie also increases oil producers’ revenue when translated into C$. In addition, costs in the oilpatch have dropped significantly. (See story on page 35.)

Thus, although Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador, and, to a lesser extent, Saskatchewan have been hit hard by the reduced oil price, economic growth has continued in other provinces. There is sufficient job creation nationwide to keep the unemployment rate at less than 7%.

Nevertheless, low oil prices and the resulting dearth of energy investment are likely to be a drag on Canada’s economy for some time.

Exports to the U.S. will be the main driver of Canada’s economic growth. Consumers will continue to increase their spending, but only modestly. Housing won’t be buoyant. Capital investment in the energy sector has been hit hard, although there will be some offset if manufacturing exporters invest in more capacity.

There could be some stimulus from the federal government, but only if the Liberals win the Oct. 19 federal election; both the Conservatives and New Democrats have promised balanced budgets.

The picture is rosier in the U.S. American consumers are in good shape. Job growth is strong, wages are rising and debt loads have dropped considerably. There is a good deal of pent-up demand for purchases put off in the years since 2008, when the global credit crisis hit, which should fuel strong consumer spending.

Gampel expects increases of 3.1% in retail purchases in the U.S. in 2016, for example, vs only 2.2% in Canada.

Depending upon exports to the U.S. for economic growth is not new for Canada, but Canada is unlikely to benefit as much as it has in the past. Although the drop in the loonie makes our manufacturing goods more competitive in the U.S., we will be competing against Mexican and European firms whose currencies have depreciated against the US$ even more than the C$ has – and we also will be competing against Chinese goods. Canada’s share of U.S. imports has dropped to 14% from 20% in the late 1990s/early 2000s.

Furthermore, you can’t sell what you can’t produce. Canada’s manufacturing capacity shrank during the years of high oil prices that pushed the loonie to around parity with the US$ – nor is there any guarantee that capacity will increase now that the C$ is low again.

“There still are risks that more capacity will leave Canada for lower-cost countries,” says Jimmy Jean, senior economist with Desjardins Group in Montreal.

These constraints on export growth are among the reasons Krishen Rangasamy, senior economist at National Bank of Canada in Montreal, is forecasting only 1.6% GDP growth for Canada next year – although he also expects energy investment to remain very weak. He has one of the lowest forecasts among the surveyed economists for the average oil price in 2016, at US$51 a barrel.

With so many constraints on economic growth, the Bank of Canada (BoC) will be cautious in raising interest rates, even when the Fed increases interest rates south of the border.

Assuming market turmoil eases, most economists expect the Fed to increase its interest rate by 25 basis points this autumn, with further increases in 2016 – although there’s considerable disagreement about how high rates will go. Some of the economists surveyed believe the Fed will raise the interest rate a couple of times and then pause to make sure the U.S. economy is withstanding the higher levels before boosting rates further. Other economists foresee a steady increase in rates through 2016. Forecasts for the U.S. three-month T-bill rate at the end of 2016 range from 0.9% to 2.1%.

None of the economists surveyed expect the BoC to move this year, and four of the eight, including Rangasamy, expect no action in 2016, either. Three of the other four expect only a modest increase next year.

However, Paul Ferley, assistant chief economist with Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto, foresees the Canadian three-month T-bill at 1.4% at the end of 2016. “There’s too much pessimism,” says Ferley, who thinks many economists are underestimating the positive effects of U.S. GDP growth. He has the highest forecast for both U.S. and Canadian GDP growth next year at 3% and 2.3%, respectively.

Ferley also has the lowest forecast for Canada’s current account deficit – $22.4 billion – reflecting the strength in Canada’s exports that he’s expecting and the upward movement he’s anticipating in oil prices, which he expects will average US$64 a barrel in 2016.

Economic growth in Canada of 2.3% sounds pretty modest, at least by historical standards. Aging populations in most industrialized countries are reducing potential growth because as baby boomers retire, there are proportionately fewer and fewer people available to work, which limits how much economic activity can increase.

Canada’s “trend growth rate” (TGR) – the average pace that can be expected over a business cycle – now is about 2%. The U.S.’s TGR has dropped to around 2.25% and the TGR is even lower for Europe and Japan, at around 1% or less, because their labour forces are shrinking. Many of the emerging-market countries don’t have this constraint on economic growth because they have young populations.

However, most emerging economies are generally in a weak growth period, partly because of low commodities prices, but also because China’s growth is slowing as it shifts to an economy led by consumer spending rather than by exports and infrastructure building.

This shift is a normal development as an economy matures, but it does spell slower global economic growth. This situation tends to feed into the overall feeling of economic uncertainty, as many investors fear even slower growth is ahead.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.