Consumer spending is supplying the muscle for economic growth in both Canada and the U.S. this year. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that businesses in the U.S. haven’t been doing their part by making investments, resulting in real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of just 1.5% or so this year in that country. This has dissuaded the U.S. Federal Reserve Board from moving ahead with long-anticipated increases in interest rates. Meanwhile, growth in Canada’s economy, which is heavily dependent on investment in the beleaguered oilpatch, is expected to be an anemic 1.2% in 2016.

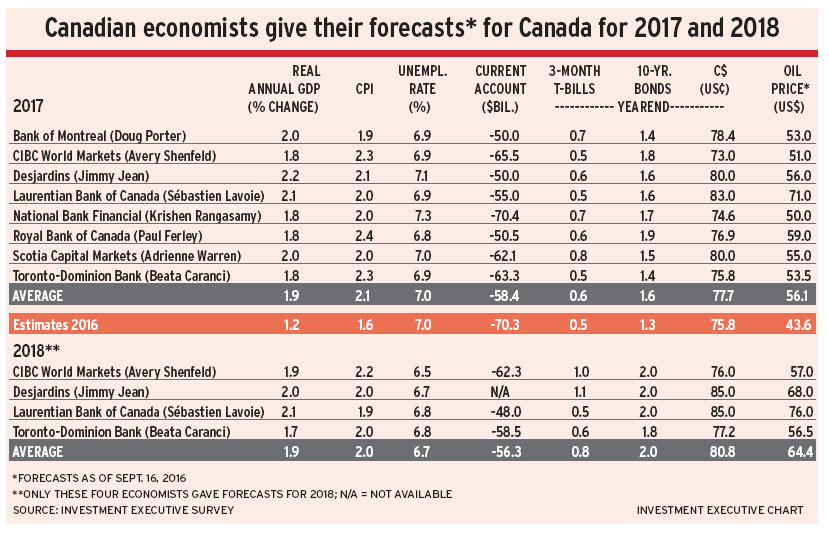

Although the outlook for economic growth in 2017 and 2018 is more optimistic, it is hardly robust. Investment Executive’s (IE) survey of eight economists produced an average forecast for real GDP growth in 2017 of 1.9% in Canada and 2.2% in the U.S. The four economists who gave forecasts for 2018 foresee virtually the same growth that year.

However, there should be sufficient jobs created to keep the unemployment rate in 2017 at about 7% in Canada and 4.7% in the U.S. (the latter down from 4.9% this year), with smaller declines in both countries in 2018.

The economists also expect the Fed to start increasing interest rates, probably in December. However, the Bank of Canada (BoC) is unlikely to do so until the end of next year at the earliest, mainly because of the prospect of weaker GDP growth in Canada.

The sluggishness of the U.S. economy is not new. “Instead of investing in plant and equipment, companies have been buying back shares,” says Jimmy Jean, senior economist with Desjardins Group in Montreal.

Adds Beata Caranci, vice president and chief economist at the Toronto-Dominion Bank in Toronto: “Demand in the U.S. is good, with personal consumption rising by about 2.7% this year, which should be an incentive for business investment. But companies remain on the more cautious side.”

This caution is understandable. Many clouds hover over the global economy, including uncertainty about the slowdown in global trade, the strength of China’s economic growth, when the Fed will raise rates, who will win the U.S. federal election and the impact of the Brexit vote on economic growth in the U.K. and in Europe.

But without more business investment, U.S. economic growth will continue to be sluggish. Medium-term growth will be compromised because there won’t the productive capacity in place to encourage faster-paced expansion.

Potential GDP growth in the U.S. has already been affected because of demographics, particularly the retirement of baby boomers. Average annual labour force growth is expected to be only 0.5% in the coming decade, vs 1% in 2002-07, according to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

That reduces the CBO’s estimate of real GDP growth to 1.8% from 2.5% in 2002-07 – assuming productivity growth of 1.7%. But investment in machinery, equipment and technology is key to achieving the productivity growth. With the lack of investment in 2008-15, productivity growth was only 1.2%.

Nonetheless, the economists surveyed by IE think U.S. business investment will improve. In fact, they believe improvement will show up in this year’s Q3 GDP numbers and anticipate that will give the Fed the confidence to start raising interest rates.

Six of the eight economists surveyed forecast a 25-basis-point increase in the Fed rate in December, probably followed by two increases in 2017. The four economists with 2018 forecasts foresee another one or two hikes in 2018 as well.

However, most of the economists surveyed don’t see the BoC increasing rates until late 2017, and a couple economists think the BoC may wait until 2019. Lower rates in Canada should keep the value of Canadian dollar (C$) from climbing too much relative to the U.S. dollar (US$) and, thus, encourage exports to the U.S.

Economists and the BoC had hoped that increases in manufactured goods exports would offset the negative economic impact of low oil prices on energy investments to some extent. Canada’s exports have become more competitive in the U.S., thanks to the drop in the value of the C$.

However, increases in Canada’s exports haven’t materialized to the extent anticipated, partly because of sluggish U.S. economic growth – but there are other factors as well.

“The C$ has dropped vs the US$, but not against many other currencies,” says Sébastien Lavoie, chief economist at Laurentian Bank of Canada in Montreal. That means other countries are also very competitive in the U.S. market.

Doug Porter, chief economist at Bank of Montreal in Toronto, agrees: “There’s fierce new competition [for Canada] in the U.S. market from Mexico and China.”

As well, Paul Ferley, assistant chief economist at Royal Bank of Canada in Toronto, says U.S. exports of consumer goods have a higher Canadian content than goods consumed in the U.S. Sluggish global growth has curtailed U.S. exports, thus reducing demand for Canadian content.

Forecasts for the C$ are relatively benign, ranging from US73¢ to US80¢ as of Dec. 31, 2017, which should keep Canada’s manufacturing exports competitive.

There could be some strengthening in 2018, with Jean and Lavoie both forecasting the C$ will reach US85¢ by yearend – still a relatively competitive level. However, Caranci and Avery Shenfeld, chief economist at CIBC World Markets in Toronto, both believe the loonie is more likely to be around US76¢-US77¢.

Important as exports are to Canada, oil prices are even more so – and prospects aren’t buoyant in the oilpatch. The economists expect oil price increases, but not to levels that will result in much, if any, oilsands investment.

There’s a wide range of oil price forecasts – from US$50 per barrel to US$71 per barrel for 2017 and US$56-US$76 for 2018. The uncertainties aren’t on the demand side, which is expected to expand in line with global growth – or somewhat less, if efforts to reduce greenhouse emissions succeed. But there are big unknowns on the supply side – particularly about at what price and how fast U.S. shale production will pick up – and when and by how much OPEC will restrain its production.

There’s no consensus on what price would result in increased oilsands investment. Ferley and Jean think there could be some uptick in investment at the US$75 and US$80 price points, respectively. But Lavoie thinks the oil price would have to move up to US$90-US$100 for several years – an increase he does not expect: “The days of strong oil investment for Canada are over.”

The other question for the Canadian economy is housing, particularly the hot Greater Vancouver Area (GVA) and Greater Toronto Area markets.

All economists surveyed foresee cooling markets this year. Caranci believes there was evidence of a slowdown in price increases in Vancouver before the Britich Columbia government imposed the 15% tax on purchases of residential properties in the GVA by non-resident foreign buyers. Caranci expects about a 10% decline in GVA prices from current levels.

Caranci thinks Toronto prices are more likely to remain around current levels because listings are contracting there while still increasing in Vancouver.

A housing-price crash is not in the cards, says Porter: “I think it would take either a significant shock, such as a global downturn, or a significant increase in Canadian interest rates to really blunt the market. And I don’t foresee either.”

But affordability is an issue, says Jean: “Households in B. C. and Ontario are taking on more risk. When the next shock comes, things could be very tough.”

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.