Global fixed-income fund portfolio managers face a challenging environment as interest rates in much of the developed world edge upward.

Yields began the year with a jump. In early February, the yield for the bellwether U.S. 10-year treasury bond was more than 2.8% — the highest level since 2014 — reflecting market expectations for a healthy U.S. economy.

The U.S. Federal Reserve Board has indicated it probably will raise its key lending rate by another three notches in 2018, following the three hikes implemented last year. Interest rates also are moving upward in Europe and Japan, where they have been in negative territory. Any rise in interest rates puts downward pressure on bond prices, which move in the opposite direction to yields.

Fed chairman Jerome Powell, who succeeded Janet Yellen this month, has been part of the consensus shaping recent Fed strategy, and he is likely to continue to increase the Fed’s benchmark lending rate, to a target range of 2%-2.5% by yearend from 1.25%-1.5%. The Fed also plans to shrink the government balance sheet’s debt by reducing the central bank’s bond-buying program.

“There’s a lot of bearish sentiment in the bond market, and much of that is based on a lot of optimism for global economic growth and expectations of rate hikes,” says Kamyar Hazaveh, vice president, fixed income, with Toronto-based Signature Global Asset Management (a division of CI Investments Inc.) and lead portfolio manager of CI Signature Global Bond Fund. “Having said that, there are elements that could contain any bond market sell-off. Global economic growth could come in below expectations, which are extremely elevated and will be hard to meet. I would not be surprised to see a reasonable year in bonds.”

Any severe stock market correction also may increase investor interest in stable, longer-term government bonds, Hazaveh adds, although a correction would likely have a negative impact on higher-risk corporate debt. Corporate bonds have risen into “expensive” territory and the yield spread (a.k.a. risk premium) relative to government issues has narrowed.

“There is a diversification benefit for investors in holding bonds in a balanced portfolio,” Hazaveh says. “If we saw any signs of economic weakness, the intention by policy-makers to hike rates would be removed and the bond market would perform nicely. The Fed’s anticipated three rate hikes are priced in, but things could change. My general recommendation is to stay diversified, as the mood can swing in financial markets from depression to optimism to mania, and a bond portfolio can be a stabilizer.”

Hazaveh also is tilting toward emerging-markets’ government bonds and away from corporates. The CI fund’s assets under management (AUM) are 87% invested in government bonds, with only 4% in corporates. Hazaveh considers the latter to be a risky asset class in this low interest rate environment, particularly after the narrowing of spreads in recent years.

“Corporate bonds in Canada and the U.S. are expensive, and we don’t want much exposure,” Hazaveh says. “Corporate bonds are pricing in ‘Nirvana’ and ‘Goldilocks’.”

On a geographical basis, bonds issued by emerging-markets countries account for about 15% of the CI fund’s AUM, Hazaveh says. In this category, he prefers sovereign bonds denominated in U.S. dollars (US$), including holdings in Argentina, Brazil, Spain, South Africa and Turkey.

“As the creditworthiness of emerging markets continues to improve, yields in emerging markets are likely to decline – and that leads to price appreciation on outstanding bonds,” Hazaveh says. “The downward turn in the U.S. dollar since the tax cuts has given emerging markets an added leg up.”

Hazaveh also is adding exposure to inflation-linked bonds, which, he says, have not priced in any significant pickup in inflation and, therefore, would offer protection if inflation delivers an upside surprise. The U.S. core inflation rate was 1.8% at yearend, less than the Fed’s target of 2%. But higher than expected inflation and the accompanying rise in interest rates to quell it are possible risks to bond prices, he says.

“Inflation-protected issues are about 10% of the portfolio, which historically is a large allocation for us and differentiates us from our benchmark,” Hazaveh says.

More than half of the CI fund’s AUM is held in North America and, for these issues, Hazaveh is focused on the “back end of the yield curve” by holding some longer-term bonds. The fund is overweighted in 30-year government bonds, which offer a higher payout than shorter-term, two- to five-year bonds, and are affected less by the Fed raising short-term benchmark rates.

The CI fund also has 6% of AUM held in U.S.-based, federally backed, mortgage-backed securities, for which, Hazaveh says, the credit quality has improved because U.S. households have deleveraged since the global financial crisis of 2008-09. These securities pay a healthier interest rate than government bonds do and tend to move in a non-correlated fashion, and so are valuable for portfolio diversification.

The CI fund is “heavily underweighted” in Japan and Europe, where, Hazaveh says, bonds are expensive and interest rates have the most room to move upward.

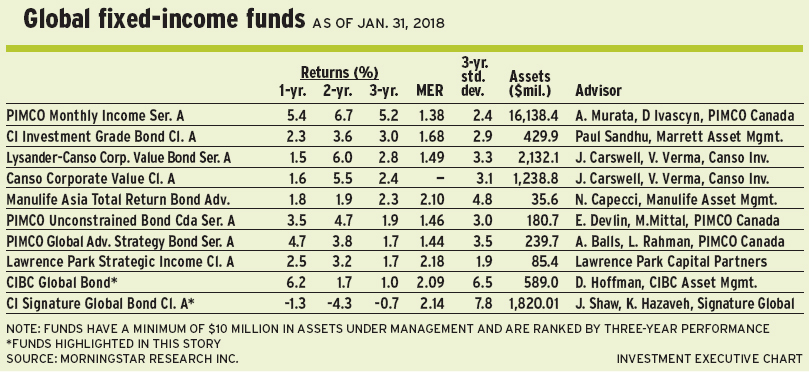

David Hoffman, Managing director and portfolio manager with Philadelphia-based Brandywine Global Investment Management LLC, subadvisor to CIBC Global Bond Fund, has positioned that fund for a rise in interest rates in the developed world as economic growth picks up and rates come off the unusually low levels they’ve held since the global financial crisis.

“Our bearish view on developed markets’ bonds is based on a rise in real yields and the possibility that inflation could pick up,” Hoffman says. “However, I don’t foresee a big jump in inflation, as there are some dampening factors, such as too much debt, technology and demographics – populations are getting older and spending less.”

Hoffman is particularly wary of corporate bonds, which, he says, are approaching the end of a long period of narrowing spreads relative to government issues. “The [debt] market has had the wind at its back, with spreads narrowing and low volatility,” he says, “but it will be hard to capture that perfect world.”

About 14% of the CIBC fund’s AUM is allocated to corporate bonds, while more than 80% of AUM is held in government bonds. Among government issues, the biggest portion – about 45% of total AUM – is held in bonds issued by emerging countries, for which yields are significantly higher. “We aren’t an emerging markets fund,” Hoffman says, “but we certainly have significant exposure to both bonds and currencies in those areas.”

The CIBC fund’s top emerging-market holding is in Mexican government bonds. There also are significant positions held in sovereigns issued by Poland, South Africa, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brazil. “We foresee negative returns for Canadian and U.S. government bonds,” Hoffman says, “and are happy to have emerging-markets exposure.”

Emerging markets’ bonds generally pay higher rates of interest and, in many cases, are issued by countries with higher rates of economic growth and lower debt levels than developed nations have. As government balance sheets continue to improve in emerging markets, there is room for interest rates to drop yet still attract lenders – a situation that would have a bullish effect on bonds.

At the same time, some emerging markets’ currencies are gaining strength relative to developed markets’ currencies as less developed countries become wealthier and healthier. As well, some of U.S. President Donald Trump’s policies are having a weakening effect on the US$.

Therefore, there is potential to benefit from the “currency effect” in bond portfolios by holding emerging markets’ bonds issued in local currencies.

“Sometimes we hedge, but we often allow for the currency effect,” says Hoffman, who estimates that, historically, up to 50% of the CIBC fund’s “alpha” (that is, outperformance) relative to the benchmark Citigroup world government bond index is due to currency decisions.

Aside from being underweighted in the bonds of developed countries, the other differentiating prong of Hoffman’s strategy is duration. He has moved the CIBC fund’s portfolio toward short-term securities to protect against future interest rate increases and the possibility of inflation being higher than anticipated. The average duration of the fund’s portfolio is 3.6 years, less than half the 7.8-year duration of the Citigroup benchmark.

“Growth is picking up around the world and wage pressures are increasing,” Hoffman says.

Even in emerging markets, Hoffman’s focus is in short-term issues and “defensive.” About 15% of the CIBC fund’s AUM is invested in floating-rate securities, which will benefit if interest rates rise.