Most advisors look to ETFs as long-term investments for clients. But with so many new launches in the Canadian market, not all of these products will survive.

“There’s no magic formula to predict whether a fund closes or stays open, merges or liquidates,” said Ryan Jackson, manager and research analyst, passive strategies with Morningstar Inc. in Chicago.

And with more and more ETFs launching, “it is part of the natural progression of the industry that some ETFs will not garner the interest a sponsor had hoped for,” said Jasmit Bhandal, chief operating officer with Horizons ETFs Management (Canada) Inc. in Toronto.

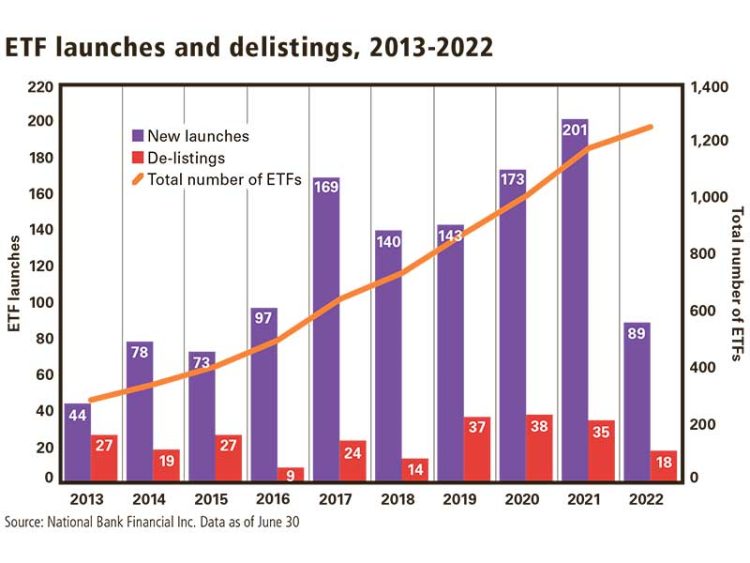

There were 1,251 Canadian ETFs at the end of June, according to National Bank Financial Inc., and ETF launches continue to vastly outpace closures. The Canadian industry launched 201 ETFs last year and 89 more in the first six months of 2022. That compares to 18 funds delisted in the first half of this year and 35 closures last year (see chart below. National Bank’s data excludes advisor-class Canadian ETFs).

How can advisors determine which funds will survive? When studying American ETFs, Morningstar found that funds with US$140 million or more in assets “tended to be much more likely to survive,” Jackson said, but added there’s no hard and fast rule.

Howard Atkinson, CEO of Pascal WealthTech and founding chairman of the Canadian ETF Association, said the threshold in Canada is closer to $50 million.

But revenue also matters. If management fees are below 10 basis points, a Canadian ETF may need more than $50 million in assets to succeed, Atkinson said. “If you have active ETFs, where the fees approach 1%, you may be able to make it on a little less,” he said.

Bhandal pointed to $100 million as an important milestone. “That’s not the minimum you need to keep an ETF going, but I would say that is considered a successful ETF,” she said.

Charging a higher fee brings in more revenue, but undercutting the competition can attract investors. Jackson said his analysis of the U.S. market between 2005 and 2020 showed “the more expensive [an ETF] was, the more likely it was to close.”

“Looking at the past decade or so, investors have wised up a little bit about the power of fees on investments,” he said. “For a long time, [fees] weren’t as heavily considered as they are now.”

Investors in Canada prefer lower-cost products, too, but high fees don’t necessarily cause ETF closures, said Daniel Straus, director of ETF and financial products research with National Bank Financial.

In National Bank’s database, the majority of ETFs that were delisted had fees of 0.5% or more. But some ETFs with higher fees “were experimental strategies or actively managed products that didn’t do well in the long run, and it was their low assets that led to their termination, not their higher fees,” Straus said.

Some funds compete more on features than on fees. Raj Lala, founder, president and CEO of Evolve Funds Group Inc., said investors should focus on a product’s merits: “I think the fees side of this business has been a little bit overdone.”

The decision to close an ETF is “part art and part science,” Lala explained. In addition to assets, managers consider the asset class and sector when predicting the likelihood that a new fund will grow large enough to break even. “It could also be [the fund is] in a category where you’re underperforming relative to your peer group,” Lala said.

Sometimes products that began well have a harder go when market conditions change. In some cases the sector “was hot when the ETF launched but then just fell on really, really bad times,” Atkinson said.

When that happens, investors often lose interest in the sector, he said, and ETFs lose assets and close. He pointed to the cannabis sector, with several products launching around the time the drug was legalized in Canada. Three of these products (two from Evolve and one from Horizons) closed in March 2020, according to Morningstar.

A potential concern for manufacturers now is that ETFs that thrived in a low-interest-rate environment may not work as well with rates rising, Bhandal said, and many categories have lost assets this year.

“Over time, you’re going to see flows into and out of categories based on what’s going on in the marketplace,” she said. “As an ETF sponsor, you want a shelf where your investors feel like they have opportunities to move within different asset categories, so you don’t have something too narrow that’s only going to work in particular market cycles.”

Another factor affecting the decision to close an ETF is its age. “Most sponsors only start looking at ETFs for closure if, two or three years [after launch], they’re not getting to the levels that they were hoping for in terms of investor interest,” Bhandal said.

“It’s kind of like the things you hear on Planet Earth or these Discovery Channel documentaries: ‘If these cubs make it past the first few years of their life, they’re much more likely to survive from then on,’” Jackson said. “It’s kind of the same idea with funds. Early on, it’s like a trial period where they’re really struggling to drum up assets. Maybe performance isn’t great right away.”

Mark Noble, executive vice-president of ETF strategy with Horizons, said he expects a large number of fund closures in the next few years. As of July 31, there were 330 ETFs in Canada with less than $10 million in assets, he said.

If those funds with “anemic assets” also underperform, they could be in trouble. “That combination is usually the death knell for an ETF sticking around,” he said.

However, Straus said some providers are willing to maintain a fund that hasn’t attracted a lot of assets.

While some providers see $50 million as a break-even, others “don’t try to consider whether any one individual ETF is self-sustaining,” Straus said.

“They want to be able to communicate to clients that they’re providing a full-service offering. ETFs are used as building blocks by many investors who are cobbling together different ETFs to build a holistic portfolio.”

How to react to impending ETF closures

When an advisor finds out their client’s ETF is going to close, they can do one of two things, said Howard Atkinson, CEO of Pascal WealthTech and founding chairman of the Canadian ETF Association: sell the ETF and redeploy those assets into a similar product, or hold the ETF until it’s liquidated.

“Because ETFs trade at net asset value, there’s no economic loss to [hold it]. Whatever the underlying assets are trading for will be reflected in the ETF price and you’ll be able to take your cash out of that ETF,” Atkinson said.

The decision — to sell early or wait until liquidation to get the proceeds — may depend on the client’s circumstances.

“There’s no big advantage of selling before the fund winds up, because it’s in our fiduciary responsibility as portfolio managers to manage it the same way with the same investment objective up until the date of the windup,” said Raj Lala, founder, president and CEO of Evolve Funds Group Inc.

An investor picks an ETF for a reason — for example, they liked the overall concept of the product or the sector in which the ETF invests, Lala said. In some cases, they may want to hold the fund until it closes if there isn’t a similar product in the market.

Depending on the fund, Lala said, investors are typically given at least 60 days notice before it closes.

In most cases, Atkinson said, if investors can find a replacement ETF, they should move into it.

Click image for full-size chart