Investment advisors place high value on having branch managers who not only provide support for practice management and staying compliant, but also act as advisors’ main connection with their firms’ head offices and inform the way advisors experience the firm’s culture.

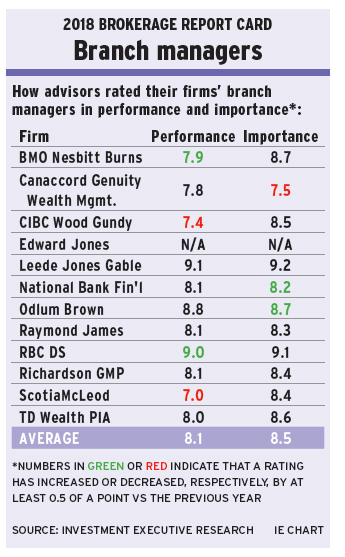

The results of this year’s Brokerage Report Card reveal that some firms have these kinds of managers more than others do. And this divergence was especially evident among the bank-owned brokerages.

Many advisors mentioned their branch’s managerial structure as a reason for their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their branch managers. Notably, some of these firms have “producing” branch managers, wherein an advisor takes on the duties of managing a branch.

Advisors at Toronto-based CIBC Wood Gundy, in particular, said this model is cause for concern. They gave their firm a rating of 7.4 in the category, down from 8.2 in 2017 and good for the second-lowest rating in the category this year.

“It’s an industry issue. People become branch managers because they’re good salespeople; they have big books,” says a Wood Gundy advisor on the Prairies. “[But] they’re not managers.”

“Having a producing branch manager is a massive conflict of interest,” adds a colleague in Ontario.

This conflict of interest could show itself in either the distribution of new assets among the branch’s advisors or in the way staffing issues are handled.

“My branch manager poached one of my employees, and the people above him did nothing,” says a Wood Gundy advisor on the Prairies.

Although advisors with Toronto-based ScotiaMcLeod Inc. also were critical of their branch managers – giving them a survey-low rating of 7.0, down from 7.7 year-over-over – some had a different take on the producing branch manager model.

Some ScotiaMcLeod branches have producing managers while others have non-producing or full-time managers. Advisors who have managers that fall in the latter group view their manager’s lack of experience as an advisor as a detriment.

“My branch manager now is non-producing, and someone who tries to do sales coaching but has never done a sale is ineffective,” says a ScotiaMcLeod advisor in Ontario.

A more prevalent complaint among ScotiaMcLeod advisors was that branch managers now prioritize the needs of the company over those of their advisors.

“Branch managers now represent the firm more than they do the advisors,” says a ScotiaMcLeod advisor in British Columbia. “[Managers] simply are an extension of the bank.”

Rob Djurfeldt, managing director and head of ScotiaMcLeod, recognizes both the responsibility branch managers have and their difficulty in supporting both the advisors and the firm.

“As a successful branch manager, you have to be balanced in supporting all the advisory teams, clients and shareholders,” Djurfeldt says. “We are running a business as well.”

Advisors with other bank-owned brokerages in the survey offered more positive views of their branch managers. At Toronto-based BMO Nesbitt Burns Inc., for example, advisors were happier with their branch managers this year, giving a rating of 7.9, up from 7.3 last year. However, there still is plenty of room for improvement. Nesbitt advisors were torn about the producing branch manager model: as many advisors praised it as criticized it.

“[My branch manager is] a producing branch manager. When I need him, he’s definitely either a good support or valuable insight, [has] good experience, a good model for what to do and what not to do,” says a Nesbitt advisor in Ontario.

However, a colleague in B.C. states: “[My branch manager has] a very large book of business. I don’t think he has enough time or really cares enough to run the branch the way it should be.”

At Nesbitt, much like at ScotiaMcLeod, whether a branch has a producing or a full-time manager is decided on a case-by-case basis. Andrew Auerbach, executive vice president and head, private client division, at Nesbitt, considers having both types of branch managers an asset for the firm.

“A producing leader certainly is walking in the advisor’s shoes and can help shape context [and] share real experiences in terms of how they’re interacting with their clients,” he says. “That doesn’t preclude the strength that non-producing leaders bring: [they] have a strong track record and background in leadership in other capacities.”

At Nesbitt, a firm that has undergone significant changes in leadership and corporate culture in recent years, the connection between advisors and their branch managers has become more crucial than ever as a result of the instability.

“The branch manager is the umbilical cord between you and head office,” says a Nesbitt advisor in Ontario.

“[My branch manager] definitely has our back,” adds a colleague in the same province. “He has a strong voice with head office, so it feels like our issues are at least being brought to the table.”

Toronto-based RBC Dominion Securities Inc. (DS) also received a higher rating this year, at 9.0 vs 8.5 last year. DS advisors offered significant praise for their branch managers’ expertise and accessibility.

“[My branch manager] stays out of the way, but he’s there when you need him,” says a DS advisor in Ontario. “He has a good understanding of [the firm] and where to get resources.

Adds a colleague in the same province: “[My branch manager is] amenable, understanding and efficient.”