For the past quarter-century, high earners in Canada assumed they would pay less tax on capital gains than on dividends.

That’s no longer the case.

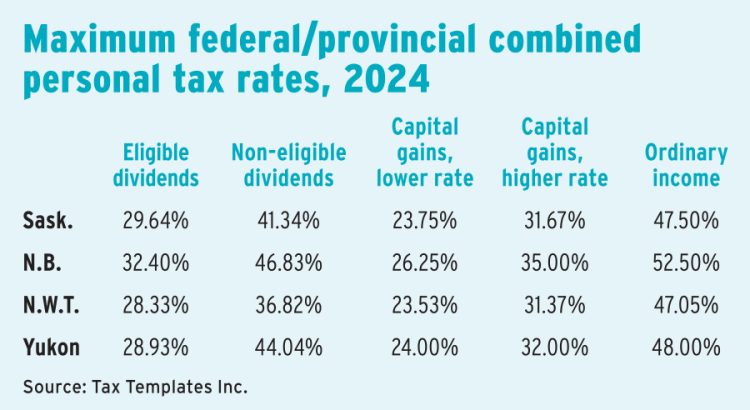

For top earners in New Brunswick, Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan and Yukon, the combined federal/provincial (/territorial) personal tax rate on the amount of capital gains over $250,000 realized in a year now exceeds the rate on eligible dividends by between two and three percentage points.

Financial advisors in these jurisdictions will have to account for this “inversion” when recommending planning strategies, said Ameer Abdulla, partner with EY Canada in Waterloo, Ont.: “In these circumstances, you may actually want a dividend, let’s say, on a sale of a business to an arm’s-length party, [when] historically, you wanted a capital gain.”

Portfolio managers may have to adjust how they assess investments. “A blue-chip stock may actually have a higher [expected] after-tax rate of return [relative to a growth stock], because eligible dividends are taxed more favourably than a top-rate capital gain,” Abdulla said.

Eligible dividends are those distributed by a public corporation or a private corporation to the extent that its income is subject to the general corporate tax rate. These dividends are eligible for an enhanced dividend tax credit.

The federal government’s decision to increase the capital gains inclusion rate (CGIR) to 66.7% from 50% on gains above $250,000 realized by an individual, effective June 25, has reduced the tax advantages of capital gains across all provinces and territories relative to dividends.

This has led to the inversion. (See table.) For example, eligible dividends in New Brunswick are taxed at 32.40%, which is 2.6 percentage points lower than the higher capital gains rate. The difference is highest in Yukon (3.07 percentage points).

None of the four affected jurisdictions introduced recent tax changes that led to the inverted rates, Abdulla said: “It’s just that provinces move in one direction based on their fiscal priorities, and the federal government moves in ways that advance its fiscal priorities, and sometimes they’re at cross-purposes.”

The last time combined tax rates for dividends were equal to or lower than the rate on capital gains was the 1990s, when the CGIR was 75%.

Back then, “there was planning [to implement] a sort of reverse surplus strip — to convert what would have been a gain into a dividend,” Abdulla said.

Ryan Minor, director of taxation with CPA Canada in Toronto, said much of the impact of the inverted rates will probably be felt when planning a business succession.

Clients selling a business may want to realize capital gains to the extent that they can access the lifetime capital gains exemption or the new Canadian entrepreneurs’ incentive, Minor said, even if the tax rate on the gains is higher.

However, beyond using the exemptions, a business owner may consider receiving at least some of the sale proceeds in the form of eligible dividends, Minor said: “Maybe you create a note with an eligible dividend and sell the note.”

Abdulla said high-net-worth clients who expect to receive significant eligible dividends could consider moving to a province with the inversion.

“At the right scale, persons who are mobile anyways [might consider] relocation — that sort of planning is not new,” Abdulla said. “This inversion adds a little bit of a twist to what locations people consider or put on their short list.”

Abdulla anticipates inverted rates will factor into discussions with incorporated clients in November and December regarding how to structure compensation.

“It’ll get a lot of traction at that point in time if people haven’t already known or been made aware of it,” he said.

This article appears in the September issue of Investment Executive.

Canada must modernize financial legislation

Opinion: Failure to adapt risks leaving the nation behind