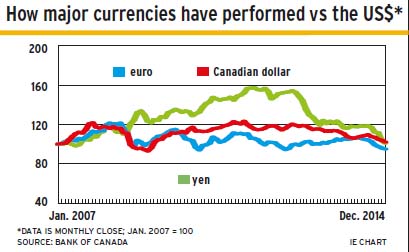

Thanks to a confluence of factors, the U.S. dollar (US$) is expected to continue to rise against most currencies, including the euro, the Japanese yen (¥) and the Canadian dollar (C$).

In particular, the U.S. is the only major country or region whose economy is accelerating, so there’s strong demand for U.S. investments. As well, the U.S. Federal Reserve Board is expected to start raising short-term interest rates sometime this year, which will increase demand for U.S. treasuries and, thus, for the US$.

In contrast, there are no reasons for other currencies to rise. Europe will be lucky to eke out as much as 1% economic growth this year and, as a result, there will be no increases to its interest rate. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is actively pushing down the value of the ¥ through an enormous quantitative easing program.

As for the C$, it’s tied to oil prices – and as almost no one expects oil prices to return to US$100 a barrel, it’s unlikely that the loonie will go back to parity with the US$. The Bank of Canada also is expected to lag the Fed in raising interest rates.

Among developing economies, the Russian ruble was pulled down by 50% with the plunge in oil prices and, although the ruble has stabilized, it’s unlikely to appreciate significantly. Brazil and Argentina also are both struggling at the moment.

It’s possible China might continue its policy of appreciating the renminbi a little each year. But with that country’s economy slowing, the government may not feel the need to so.

Another reason for the strength of the US$ is that it’s also the world’s reserve currency. Thus, it’s considered a safe haven for investors concerned about economic, financial and geopolitical risks. The US$’s only competitor is gold, but the fundamentals for gold currently aren’t positive. At best, gold is expected to trade in the range of US$1,100-US$1,300 an ounce; some analysts predict the price of bullion might move lower.

A rising US$ is good for most economies because that makes their exports to the U.S. more competitive and makes their home-produced goods more competitive against American imports. That’s the reason the BoJ is pushing down the ¥ and why Europe welcomes a lower euro.

A lower C$ is a boost for Canadian manufacturers that export to the U.S. or compete against American goods.

For investors outside the U.S., a rising US$ is positive because it enhances returns when translated into their domestic currencies. For example, a 5¢ drop in the C$ vs the US$ over the course of a year will provide an increase of five percentage points in the return of US$-denominated investments in C$ terms.

So, if the C$ is trending downward, there’s no need to hedge against U.S. investments. The question is whether Japanese and European investments should be hedged – and that depends on whether the ¥ and the euro will drop more against the US$ than the loonie does.

Generally, portfolio managers and global strategists advise hedging your Japanese investments because there could be further significant drops in the ¥. However, there’s no great need for European investments to be hedged, as the euro and loonie could move in lockstep.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.