THE GLOBAL ECONOMIC OUTLOOK for this year is mostly positive, with many economists calling for continued growth and less uncertainty.

Although there is wide agreement that investment returns in equities markets are unlikely to match the strong surges of last year, portfolio managers say, total returns of 7%-10% are likely. Many regarded last year as a catch-up year, with long-depressed stocks, particularly in Europe and Japan, rebounding. U.S. equities also did well. It was only emerging markets and resources-producing countries such as Canada that were down or less buoyant.

The key to maintaining solid returns this year is continued acceleration in global growth – to 3.2%-3.5%, compared with the estimated 3% last year. Achieving this level of growth will depend on the U.S. and China.

“This is a U.S.- and China-led recovery,” says Drummond Brodeur, vice president, portfolio management, and global investment strategist with Signature Global Advisors, a unit of CI Financial Corp. in Toronto. “No one else matters.”

The U.S. and China are the world’s largest economies, and many countries depend on exports to the U.S. and China to keep their economies growing. This is so even though China’s growth rate slowed to around 7.5% last year, down from its double-digit pace in the first decade of this century. But even if China’s economic growth rate drops slightly this year, 7%-7.5% growth remains strong.

At the same time, China will be relying heavily on its exports, which account for about 40% of its gross domestic product (GDP). And as a large chunk of those exports are to the U.S., China will be dependent on continued economic recovery in the U.S.

The U.S. is not in the same boat. With its exports accounting for only about 14% of GDP, domestic demand is the U.S.’s main growth driver. That economy is expected to grow by 2.5%-3% this year, up from 2013’s estimated 1.7%.

The eurozone, on the hand, remains sluggish, even though it is one of the world’s largest markets. This region is expected to post positive GDP growth of 0.5%-1% this year. Although that doesn’t sound impressive, it’s a significant turnaround when compared with its estimated 0.5% decline in 2013.

Japan is a question mark. The Bank of Japan is aggressively printing money and the country’s government, under new prime minister Shinzo Abe, is implementing financial measures designed to promote economic growth. But a sales tax increase coming in April, to 8% from 5%, is likely to have negative impact.

Overall, emerging economies are expected to post stronger growth rates than those in the industrialized world, although they won’t be growing strongly.

However, this picture of widespread growth is not expected to be strong enough to boost the prices of commodities, which remain lacklustre and still depressing the value of many resources-based stocks.

Opinions among portfolio managers vary, however. Jean-Guy Desjardins, chairman, CEO and chief investment officer (CIO) with Fiera Capital Corp. in Montreal, thinks the U.S. economy will grow by 3.5%-4%, thus contributing significantly to total global growth of 3.75%-4%. That situation would be sufficient to push up resources prices and, as a result, his portfolios are overweighted in energy and base metals.

Conversely, Ross Healy, chairman of Strategic Analysis Corp. in Toronto, and Nandu Narayanan, CIO with Trident Investment Management LLC in New York and portfolio manager of a number of funds sponsored by CI Investments Inc., both think the economic outlook is very bleak because of the failure of the U.S. and the eurozone to address their debt issues in a serious manner. Both these portfolio managers think that there will be another global credit crisis in the near future, although not necessarily this year.

If they’re right, this would be a good time to buy gold. Both Healy and Narayanan foresee gold prices moving up sharply if their negative outlook becomes more likely. Narayanan expects gold bullion to reach US$2,000 an ounce in the next few years, up from its recent US$1,200 an ounce.

But other portfolio managers are not interested in gold bullion. They recommend overweighting equities, particularly cyclicals (except for resources). However, opinions are divided regarding which geographical areas offer the best opportunities. Some favour the U.S.; others think that the U.S. market is fully valued and see better opportunities in Europe and Japan.

Most portfolio managers don’t suggest currency hedging except for exposure to the yen. (See story on page B14). The yen was down by 17.6% against the U.S. dollar (US$) in 2013 and is expected to drop further in relative value this year. The Canadian dollar (C$) also is expected to decline vs the US$. However that would enhance returns for your clients when investment gains in US$ funds are translated into C$. The euro also is expected to decline relative to the US$, but not necessarily by more than the C$.

The outlook for fixed-income investments is murkier. Medium- and long-term bonds have already lost value due to the rise in interest rates. Most portfolio managers and strategists expect further losses in these investments as rates continue to rise gradually. Some recommend that investors commit 5%-10% of their portfolios to high-yield bonds, arguing that with global growth more likely to become self-sustaining, the risk of defaults is relatively low. Other portfolio managers are staying with safer bonds – particularly, those of investment-grade. Narayanan, for one, prefers an overweighted position in government bonds of “safe” countries such as Canada, Australia, Norway and Sweden.

The only consensus on bonds is keeping duration short so that losses are minimized as interest rates rise. (See story on page B16.)

Healy is nervous about bonds of more than three or four years in duration. His approach, for now, is to receive income from safe, blue-chip stocks such as Canadian banks. If your clients want to invest in U.S. equities, he suggests doing so by buying units in a currency-hedged, exchange-traded fund.

Next: The outlook for major regions and asset classes

@page_break@

The outlook for major regions and asset classes

Here’s a look at the outlook for major regions and asset classes in more detail:

– The U.S. Everyone is counting on the U.S. to push global economic growth high er. Some fiscal drag will continue as government spending remains constrained, but that will be less than in the past two years. This drag also will be offset by growing momentum in the private sector. The housing market is improving, consumers are increasing their spending and, as long as global economic growth continues at a good pace, exports should continue to rise.

One big question mark is businesses’ capital spending. Non-financial corporations still are sitting on lots of cash, so they have the potential to invest in new plants, equipment and technology and to hire more workers. But many companies continued to rein in their spending last year. The U.S. government’s 16-day shutdown last October also did nothing to promote confidence in the country’s economic outlook.

This year may be different. Economic recovery appears to be more entrenched, and the Democrats and Republicans have made some sort of peace until after the upcoming mid-term elections in November.

Another major question mark is inflation. If financial markets start worrying about inflation, they may push interest rates up by too much as the U.S. Federal Reserve Board takes tapers off its quantitative easing (QE) program. In theory, inflation should not be an issue – there still is significant excess capacity in plants and equipment, which constrains the ability of companies to raise prices; and the unemployment rate of about 7% is still too high to allow workers to demand strong wage increases.

Nevertheless, the risk of financial markets getting spooked by increases in inflation – even if it remains below the Fed’s 2% target – is real. The 10-year T-bill rate jumped by 50 basis points (bps) in the month following the Fed’s announcement last May that it was considering tapering its QE program and had risen by another 50 bps by yearend. Many portfolio managers don’t think that another 50-bps increase in long rates would derail the recovery – but anything more could send the U.S. economy into recession.

U.S. stock markets had a strong run last year. Some portfolio managers, including Brodeur and Craig Basinger, CIO at Richardson GMP Ltd. in Toronto, think there may be one or more market corrections. Brodeur thinks there could be some “healthy” corrections of up to 12%. Basinger strongly recommends having cash on hand to take advantage of resulting opportunities.

Nevertheless, Basinger is overweighted in U.S. equities, as are Sadiq Adatia, CIO at Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc. in Toronto; Lloyd Atkinson, an independent financial and economic consultant in Toronto; Desjardins; Stéphane Marion, chief economist and strategist with National Bank of Canada in Montreal; Peter O’Reilly, head of the global equities team for I.G. Investment Management Ltd. in Dublin; and Jurrien Timmer, director of global macro and portfolio manager with FMR LLC in Boston.

– Eurozone. Economic growth of 0.5%-1% isn’t going to make much of a dent in unemployment or enable governments in this region to pay off debt. These issues underline one of the region’s greatest problems: demographics. In 2013, the region’s working-age population shrank – and that trend will continue for the next 10 to 20 years. It’s very difficult for economies to grow when they have fewer and fewer workers.

Then there’s the difficulty in getting 17 countries to agree. More co-ordinated fiscal policy is urgently needed, but politicians are loath to give up power. For now, everything depends on Germany continuing to support periphery member countries.

Nevertheless, quite a few portfolio managers are overweighted in European securities. Although the region is “still a mess,” Timmer says, it’s currently one of his favourites because the eurozone has more upside than the U.S., given that the former is in an earlier stage of economic recovery.

Tony Elavia, executive vice president and CIO with Mackenzie Financial Corp. in Toronto, expects continued volatility in eurozone equities, but he is still finding opportunities in value (vs growth) stocks.

Charles Burbeck, co-head of global equity portfolios with UBS Global Asset Management (U.K.) Ltd. in London, is overweighted in the eurozone and is taking “big bets” in periphery countries. He likes consumer durables and banks, noting the opportunity to buy the latter before the results of the European Central Bank’s stress tests are released next autumn.

Other portfolio managers overweighted in the eurozone include Basinger; Timmer; and Stephen Way, senior vice president and portfolio manager, global equity funds, with AGF Management Ltd. in Toronto.

– Japan. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government was elected in December 2012 on the promise to get Japan’s economy going. The Bank of Japan is injecting huge liquidity into the system through a form of QE. This brought the yen down by 17.6% over the past year, thereby enhancing profits for exporters, producing a fourth consecutive quarter of real GDP growth in the third quarter of 2013 and pushing Japanese listed stocks on the broad Topix index up by 51% during the year.

Adatia, Basinger, Burbeck, Desjardins, Narayanan, Trimmer and Way are all overweighted in Japanese securities, but Adatia is reducing his exposure. Timmer had been overweighted but doesn’t like the prospects.

The question is whether economic growth in Japan will continue. Abe’s proposed reforms include opening the economy to foreign competition, lowering corporate taxes and encouraging women to enter the labour market.

However, government debt is already more than 200% of GDP. Most of it is held domestically, thanks to high household savings rates. But this level of debt has to be addressed, so the sales tax will rise to 8% from 5% in April and to 10% in 2015.

The big risk is flight of capital, says Brodeur. At some point, consumers alarmed by drops in the yen will want to protect the value of their savings by investing elsewhere.

– China. This country is in transition, moving to more reliance on domestic demand and less on exports and infrastructure spending. This means slower, albeit significant economic growth of around 7%.

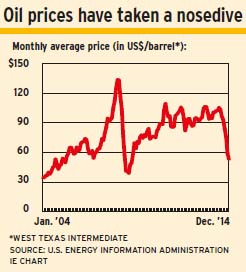

Slower growth in China will mean decreasing demand for imported resources. The big changes to impact resources prices are more likely to be technological breakthroughs that increase supply by lowering costs, says Leo de Bever, CEO and CIO of Alberta Investment Management Corp. in Edmonton. He thinks oil prices could drop to US$70 a barrel at some point.

Social unrest is always a threat in China. However, some reforms are underway. These include better wages and benefits for the huge numbers of workers moving from rural areas to cities; these workers typically have found themselves at a disadvantage relative to workers already well established in urban areas.

The “one child” policy also has been loosened. (See page B7.) This change is needed to ensure that the working-age population keeps growing.

Way is the only global portfolio manager who is overweighted in China. It is an undervalued market, he says, but warns that there could be volatility in the region. Most other portfolio managers are neutral or, like de Bever, prefer to invest in foreign companies benefiting from China’s growth rather than in China-based companies.

– Other emerging economies. The big risk for these countries is further outflows of foreign capital into U.S. investments, attracted by rising U.S. long rates.

Countries with large trade deficits, such as Brazil, India and Indonesia, are particularly vulnerable. Capital outflows bring down the value of a currency – and that increases the prices of imports.

Narayanan is overweighted in emerging-market equities; however, most other portfolio managers are underweighted.

Way is finding opportunities, particularly in northern Asia, but warns that returns on invested capital and margins are dropping in many of these countries, which is unlikely to be reversed without financial reforms. He’ll be watching the elections this year in India, Thailand, Indonesia and Brazil to see if there’s any commitment to reforms.

There is enthusiasm for this region’s debt because interest rates are more attractive in those countries. Narayanan is doubly overweighted in this debt, and many other portfolio managers are using it to increase the yield on the fixed-income portions of their portfolios.

But it’s important to factor in the possibility of further declines in currencies and to keep exposure to this and other high-yield debt to 5%-10% of client portfolios.

© 2014 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.