Bonds barely pay their way in today’s ultra-low interest rate environment. So, why should you urge bonds on your clients? The reason is they offer predictable income and return of principal; and, in these uncertain times, those are precious qualities.

Consider investment-grade corporate bonds. A Rogers Communications Inc. 10-year issue pays 3.42%, while yields rise to 5.77% for long-dated debt of real estate firms such as Brookfield Asset Management Inc.

On the other hand, Government of Canada bonds, with their annualized yields of 0.9% for 30 days and 2.39% for 30 years, are no longer about income or capital gains; now, they are about only risk aversion and safety.

There is no winning in governments at the moment. Clients either can go relatively short-term and get a negative real return or they can go longer-term and either be satisfied with a yield to maturity that, at best, barely covers inflation or take losses when they sell to buy bonds with higher coupon rates when interest rates rise.

Given these choices, it’s surprising there’s so much demand for government bonds. But there are clients who fear we are facing deflation or some other apocalyptic event and in such dire conditions, government bonds may be the only way to preserve their capital. Such clients also believe there’s little to gain in stocks and don’t trust other asset classes; so, from their perspective, the cost of low-yield bonds is minimal.

In addition, many investment strategists still recommend that your clients hold some government bonds for safety.

However, the bulk of the demand comes from financial services institutions, such as banks and insurance companies, which are subject to regulations that give greater weight to government bonds as capital reserves than to corporate bonds. The more government bonds these institutions hold, the less capital they need to make loans or to cover future liabilities. Moreover, pension funds and insurance firms have been disappointed with a decade of low equities returns and thus prefer to be overweighted in bonds and underweighted in equities.

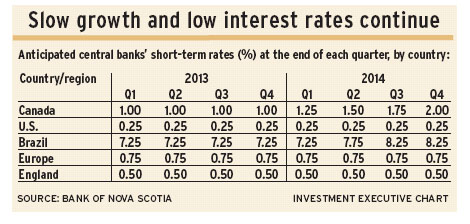

Low interest rates will be with us for a while. For those who parse the statements of the Bank of Canada (BoC) and the U.S. Federal Reserve Board (the Fed), significant rate increases are not in the cards. Indeed, the Fed has said it won’t raise its benchmark short-term rate until 2015 at the earliest.

“The global debt supercycle,” says Paul Taylor, chief investment officer, fundamental equities, with BMO Asset Management Inc. in Toronto, “will restrain rates for the foreseeable future, which is three to five years.”

In this new world in which government bond yield is divorced from risk and macroeconomics and regulated institutions are prepared to accept zero yields there’s a place for real-return bonds (RRBs). Government-issued RRBs recently paid 0.4% plus the inflation premium of 2.3% for a total return of 2.7%.

@page_break@RRBs have the characteristics of long bonds and also provide inflation insurance for pension funds and anyone else who worries that prices will take off one day. For the 10 years ended Dec. 31, 2012, RRB portfolios generated a 3.04% average annual compound return vs the 2.6% average annual compound return generated by Canadian broader fixed-income portfolios.

Unfortunately, there are few RRB issues and they are relatively illiquid. But RRBs remain valued assets, given the security they provide against inflation. The exception is during periods of deflation; when prices are falling, the value of RRBs also drop.

A more accessible option for clients looking for safety with a significant boost to yield are provincial bonds. For example, an Alberta 8% bond due Sept. 8, 2023, recently has been priced at $148.20 to yield 2.78% to maturity, which is a pickup of 100 basis points (bps) over a Government of Canada 8% issue maturing June 1, 2023, that recently has been priced at $159.13 to yield 1.78% to maturity.

These are remarkably wide spreads that reflect investor fear that worsening provincial finances may push the spreads even wider. In better times, provincial spreads over federal bonds range from 20 bps to 40 bps. The widest spread, 155 bps, was reached in early 2009.

Meanwhile, corporate bonds still have good prospects for income and capital appreciation. A-rated issues currently provide the yields that government bonds used to. But you have to be careful, says Tim Hicks, vice president with Richmond Hill, Ont.-based Canso Investment Counsel Ltd.: “We normally shy away from resources companies that have revenue tied to their [underlying] commodities. We do like consumer staples, such as Loblaw Cos. Ltd., Rogers and Shaw Communications Inc. all BBB[-rated] issues at the lower end of the investment-grade range.”

For clients who want the customary combination of bond security and income, weighting is critical. For instance, Chris Kresic, partner and head of fixed-income with Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. in Toronto, has raised his corporate bond weighting in the funds he manages to 50%, maintained federal bonds at 40% and dropped provincials to 10%.

Kresic’s concern with provincials is not based on a potential default, as no one reasonably expects any province to miss a payment. Rather, Kresic recognizes that provincial finances may worsen and that federal/provincial spreads may widen. But for your “buy and hold” clients, provincials offer unusually wide spreads and relatively good absolute returns.

The question facing every client who invests in investment-grade debt is when will interest rates rise toward the levels at which there is a positive real return on capital.

Predicting interest rate movement isn’t easy. A review by New York-based Bloomberg LP in November 2012 of surveys of economists’ views on interest rate trends found that 97% of surveys since December 2002 showed a consensus for higher U.S. bonds yields. Only 3% of surveys predicted lower rates.

But economists use conventional macroeconomic tools, which say that accommodating monetary and fiscal policy eventually work. These models don’t factor in credit collapses in Europe, angst over the U.S.’s public and private debt, and the willingness of corporations to borrow at low rates and then hoard cash rather than invest the cheap money.

“There is a tendency to believe that negative real returns on bonds cannot persist, that rational investors will not buy into guaranteed losses,” says Tony Warzel, president, CEO and chief investment officer with Winnipeg-based Rival Capital Management Inc. “But those models don’t accommodate markets for government bonds that are driven by concerns for regulatory compliance and not the old-fashioned idea of making money.”

Timing aside, it is certain interest rates will rise someday, so there is duration risk in bonds. The longer the average duration in a bond portfolio, the higher the risk. So, portfolio managers are staying short. Says Rémi Roger, vice president and head of fixed-income with Seamark Asset Management Ltd. in Halifax: “My portfolio duration, 6.3 years, is shorter than the DEX universe bond index duration of 6.9 years. But I have my duration exposure in provincials because they’re cheap [relative to Canadas].”

There is also the question of sectoral exposure. For Kresic, there are good buys to be had in financial services and telecommunications firms such as BCE Inc. and Shaw; and in insurance companies such as Manulife Financial Corp., Sun Life Financial Inc. and Great-West Lifeco Inc.

© 2013 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.