Emerging markets have historically exhibited a higher degree of volatility than developed markets, causing them to be labelled as a high-risk investment.

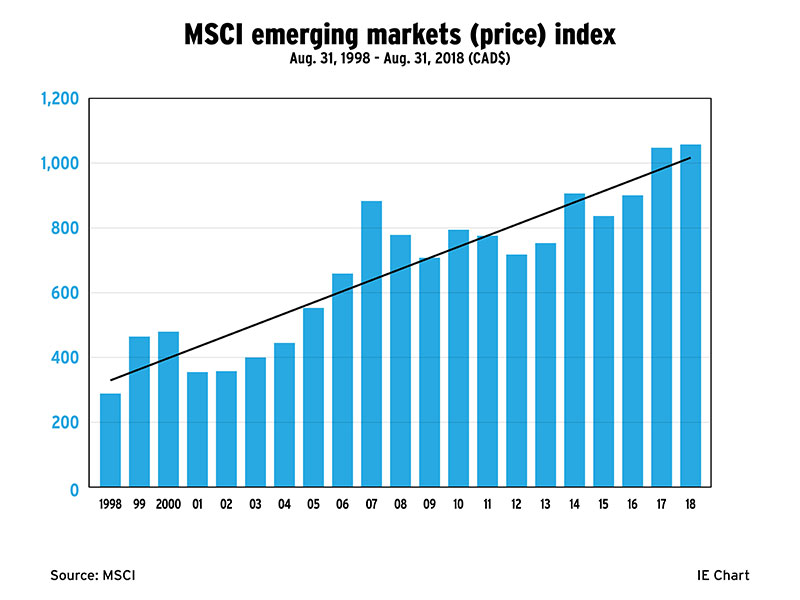

But despite the periodic ups and downs, emerging markets have trended higher over time, providing long-term investors with greater risk-adjusted returns than developed markets. In fact, the MSCI emerging markets index has risen to 1,057.54 on Aug. 31 up from 288.7 on Aug. 31, 1998 — a 266% increase over 20 years.

To put the current volatility of emerging markets into perspective, the emerging markets index began 2018 at 1,112.94 and has remained above the 1,000 mark since, with a low of 1,028.01 on Aug. 17 and a high of 1,205.21 on Jan. 26.

According to Christine Tan, associate vice president and portfolio manager with Sun Life Global Investments (Canada) Inc. in Toronto, the gross return for the MSCI emerging markets index for the 15-year period ended July 31 was 10.2%, compared with 8.2% for the MSCI world index (total return). Emerging markets also outperformed developed markets during the 20-year period, with a return of 8% vs 5.2% on the respective MSCI indices.

Investors who remain invested through several market cycles are likely to realize better returns than those who invest during market upswings and get out during market downturns, Tan says.

But moving in and out of emerging markets is typical investor behaviour, according to Matthew Strauss, vice president and portfolio manager with CI Investments Inc. in Toronto. “When emerging markets are in an up cycle,” he says, “investors looking for places to park money invest indiscriminately in these markets.”

But, he adds, they pull their money out during downturns, which exacerbates volatility further. In these instances, investor sentiment adds to the volatility of emerging markets, reinforcing the perception that they are risky.

In most instances, the cause of volatility is restricted to individual markets or regions. But negative investor sentiment tends to drag all emerging markets down. For example, at a country level, recent volatility has been driven by currency weakness in the Turkish lira, the Argentine peso, the Indonesian rupiah and the South African rand — triggering volatility across the emerging markets universe.

On the flip side, says Chetan Sehgal, senior managing director of Franklin Templeton Emerging Markets Equity in Singapore, a division of Franklin Templeton Investments Corp., escalating trade tensions, rising interest rates and a stronger U.S. dollar “may also have an adverse impact on sentiment toward emerging markets.”

During such periods, investors in emerging-markets equities generally display heightened risk aversion and engage in indiscriminate selling, often at the expense of solid fundamentals. In such cases, “volatility could present buying opportunities for long-term investors.”

Arup Datta, senior vice president and head of Mackenzie Investments’ global quantitative equity team in Boston, agrees: “Emerging markets valuations currently look pretty cheap in the wake of current volatility.”

When emerging markets are underperforming, there is usually a “longer-term window for an extra bump,” Datta adds. To take advantage of such conditions, he recommends that investors have exposure to various markets. They should “buy on dips” and use dollar-cost averaging to even out long-term returns. “Look at relative valuations compared with other regions,” he says.

The key to investing in emerging markets, Tan adds, is “not to focus on the volatility of the asset class. Think of how emerging markets fit into a diversified portfolio whose asset mix has a low correlation, in order to improve overall risk-adjusted returns.”

Emerging-markets volatility also can be triggered by several other factors. Political risk, for example, which is unique to each country or region, remains a challenge in emerging markets in general. So is geopolitical risk, which can have broader global implications.

Strauss adds that dependence on global capital — which is less a factor in Asia than in other regions — also increases emerging markets countries’ vulnerability to capital outflows. These outflows can be triggered by rising U.S. interest rates, a strong U.S. dollar and weakness in local countries, which could send their borrowing costs higher.

The underlying problem is that emerging markets are not as efficient as developed markets, according to Strauss.

“The dedicated pool of emerging markets investors is not as big as the global pool of investors,” he says. This disparity leaves emerging markets with less investor support during periods of turmoil. At the same time, emerging-markets investors normally head for safety in developed markets when emerging markets are volatile, creating a vicious cycle of volatility for emerging markets.

“Anything that can disrupt the global system can trigger emerging markets volatility,” Tan says.

She advises that investors who are concerned about volatility in emerging markets must recognize that emerging markets are not a uniform asset class. Although most emerging markets now have a domestic component to their growth, these markets do not move in sync with each other.

“Some sectors, such as consumption, technology and healthcare, are less cyclical,” Tan says, “and, consequently are less volatile.”

This is the second in a four-part series on investing in emerging markets.