Bond markets have entered a time of trouble. Bond price trends have split, with prices of U.S. government treasuries and some Government of Canada issues rising while credit rating-sensitive corporate issues have lost value in a rush to safety.

This split leaves financial advisors with a dilemma: recommend to your clients that they scoop up bargains; or stay in cash while waiting for further drops in bond prices.

There are two conflicting factors that are driving this investing climate, whether it be for stocks or bonds. On the one hand, there’s the incentive for clients with cash to go for bargains, picking up yield in solid dividend stocks and higher returns to maturity from credit rating-sensitive bonds. On the other hand, there also is a strong incentive for clients who saw their balance sheets shredded by the downturn in stocks this past autumn to play it safe.

Therein lies the conundrum, given that right now, only sovereign debt looks safe. The Toronto Stock Exchange and even major U.S. stock indices may fall further if energy prices continue their tumble, imperilling corporate bonds in that sector and turning some with high yields into no yields by default. The increase in the U.S. Federal Reserve Board’s overnight rate to 50 basis points (bps) from 25 bps this past December delivered what the market expected and set the stage for further monetary tightening.

“If U.S. unemployment numbers move downward consistently from their recent 5.1% level, then the Fed could raise its short rate again,” says Chris Kresic, senior partner and head of fixed-income with Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. in Toronto. “The Fed’s Open Market Committee has eight meetings in 2016 and could raise the overnight rate at any or all of them. The broad market is expecting as much as another 100 bps of tightening in 2016.”

Yields going the wrong way

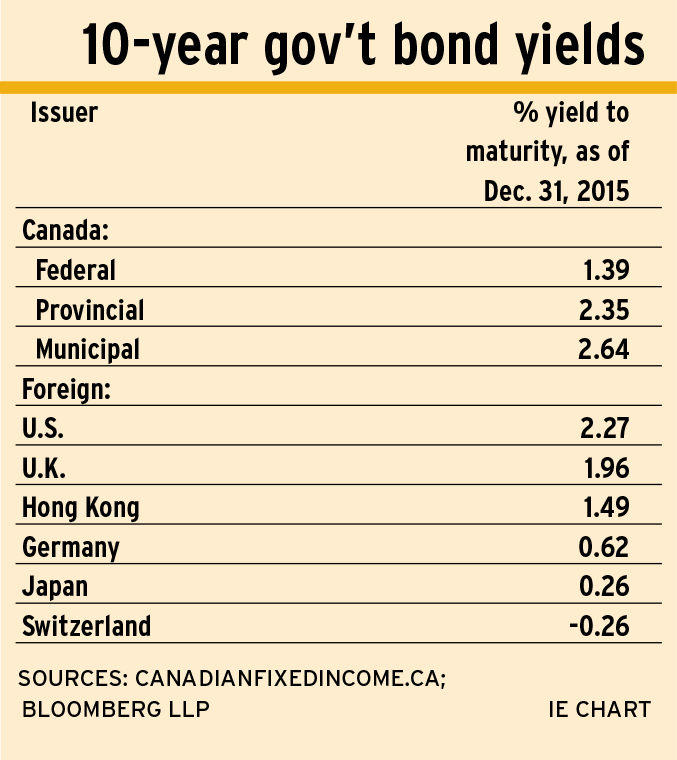

The performance of U.S. 10-year Treasury bonds, a bellwether indicator of the balance of risk and return in global capital markets, is revealing. On Dec. 16, 2015, after the Fed raised the overnight rate, 10-year treasuries traded at a 2.3% return to maturity, close to their 12-month low. Little had changed by Dec. 31, when 10-year treasuries traded at 2.27%. In the face of what is seen as an inevitable, if perhaps bumpy road to higher U.S. rates, treasuries’ yields have gone the wrong way.

Investors should be selling these riskless bonds, which are the most liquid asset in the world, rather than chance losses as new bonds come out with higher interest rates, thus dropping yields on existing bonds. Instead, investors have bought U.S. treasuries, apparently out of a feeling of distress that U.S. economic growth could falter, China’s economic growth could slow further and that the entire bond market will shun risk as high-yield bonds default. In Canada’s bond market, the rush to safety shows up in a sell-off of provincial bonds. Bond markets have shunned non-sovereign government bonds whose issuers can tax, but not print money.

In the midst of this tug of war between the desire to keep up with rising interest rates and the need for security is the essential task of asset and risk allocation.

Choices must be sensitive to the risk tolerance of each investor, but core allocation choices depend on underlying interest rates and sectoral risk.

“For most retail investors who are in buy-and-hold accounts, go for security in a 20% weighting of Canadian governments and provincials, 50% in investment-grade corporates for income and a speculative weight of 30% in high-yield bonds that are not in the commodity or energy sectors,” suggests Edward Jong, vice president and head of fixed-income with TriDelta Investment Counsel Ltd. in Toronto. “[This strategy will] take advantage of the widespread sell-off in that tier of the market.”

Canada will follow eventually

Eventually, Canadian interest rates will follow U.S. interest rates, but the timing depends on energy prices and the orderliness of the decline in the value of the loonie relative to the U.S. dollar. Says Kresic: “If [the loonie] falls faster than terms of trade justify, then the Bank of Canada [BoC] might have to raise rates to defend the loonie.”

Term and duration for this market need to be timed carefully. For Canada, the best place to be on the yield curve is on the belly, with duration of six years and a seven-year term, Kresic suggests. For U.S. issues, he suggests a barbell of 65% in two-year maturities and 35% in 30-year treasuries. The shorter-term position allows the investor to roll into higher rates, he notes.

If Canada’s economy does not follow the U.S. recovery, the BoC could push overnight interest rates down into negative territory, as BoC governor Stephen Poloz warned on Dec. 8. There is a risk that such a move could trigger the Keynesian liquidity trap, wherein people and companies withdraw money from banks entirely and put their cash under the proverbial mattress.

How serious is the liquidity trap threat? Investors scared by collapsing stocks are willing to pay for security. Switzerland offers negative yields on its government bonds for periods from one day to 10 years. It uses negative interest rates to force down the Swiss franc in order to maintain trade with neighbouring nations, especially those in the European Union (EU). (Switzerland is not an EU member state.)

Senior EU member states’ banks have used negative interest rates to encourage equity investment. Germany (negative out to seven years), France (negative out to four years), and Italy (negative out to two years) have used this policy to stimulate their economies.

However, going negative is a “beggar thy neighbour” policy: to weaken a currency, a nation’s central bank has to be more negative than the European Central Bank (ECB). So, for example, with the Dec. 3 ECB cut on charges to 0.3% for overnight loans to commercial banks, the short-rate floor in the Czech Republic is minus 0.5%; in Denmark, it’s minus 0.75%.

Negative nominal rates would be unfamiliar in Canada. Depositors could bank in another currency that pays more interest or that appreciates against the loonie – the greenback, for example. But taking cash out of the banking system altogether is not workable. There is no mattress big enough to hold the balances of corporations and institutions.

A significant impact

A move to negative nominal interest rates nevertheless would have significant effects on the yield curve. The overnight negative rate that drops the front end of the yield curve would steepen the curve. That implies higher term spreads, so money would earn relatively more for being parked for longer terms. That situation also would encourage savers and others holding substantial deposits to invest in equity positions – that is, to take on more risk to get a return.

Low and possibly negative nominal interest rates should encourage clients to buy preferred or common shares offering greater risk than bonds. But that strategy is unlikely to work if weak equities markets threaten to cut share prices by more than the dividend pickup over low or negative deposit interest rates.

© 2016 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.