For fixed-income investors who want the assurance of payment by governments or large corporations that have issued investment-grade bonds, these times are vexing. The question of what investment-grade bonds to buy inevitably is a matter of credit and time analysis.

Today, the problem is unusually severe because if economic recovery proceeds and rates rise, existing bonds are likely to lose value. Yet, if the recovery falters and deflation breaks out, as it has in parts of Europe and could in Asia, existing government bonds would gain value, being gold-plated promises to pay interest and refund principal, while many corporate bonds would lose value.

The fulcrum of the issue is the state of the world economy, in which there is excess capacity, which could keep global economic growth sluggish.

The majority of economists have held the view each year since 2009 that rates would rise in the next year or two, making the preferred terms short and the best debt investments to be corporate bonds with attractive spreads over government bonds.

However, rates have not risen in any uniform way. Quantitative easing programs have held down the short end of the yield curve, making short-term debt safe but not profitable.

Yet, long bonds in Canada and the U.S. have been turning in record profits, as banks, insurance companies and pension funds have turned to government issues to match these companies’ liabilities. For the year ended Dec. 31, 2014, the FTSE/TMX (formerly the DEX) long-term bond index was up by 12.6%.

Thirty-year U.S. Treasury bonds gained 29% for 12 months ended Nov. 30, 2014. If rates rise as expected, those gains will tend to hold, sustained by continuing institutional demand for long bonds, says Neil Bouhan, vice president of fixed-income strategy in Chicago with BMO Capital Markets Corp., a subsidiary of Toronto-based Bank of Montreal. Bouhan’s view, widely held, is that long debt issues are rare and on a continuous bid regardless of return.

Bond investors fall into two camps. The first is those who accept that 10-year Bank of Canada (BoC) and U.S. Treasury rates will normalize in the next two years around the long-term average bellwether rates of 3% and 3.5%, respectively.

The second camp takes the view that deflation – which means prices will be lower next year than they are this year – will cloud the bond market and leave rates compressed around where they are now. Deflation already has broken out or is threatening in many European countries. (See story on page B5.)

Those markets are, of course, distant and not determinative of what the BoC and the U.S. Federal Reserve Board may do in the months ahead. But Canada is suffering the effects of falling global energy prices; and the U.S., with its currency ascending against most others, has negative pressure on that country’s consumer price index.

“The rising U.S. dollar is deflationary, because it means that consumers can pay less and spend less for the same basket of goods,” says Benoît Poliquin, chief investment officer (CIO) with Exponent Investment Management Inc. in Ottawa.

The consensus among economists is that rates nonetheless will rise in 2015, probably in the second half. The Fed is expected to begin active flattening of the yield curve by raising the overnight rate and selling a chunk of the central bank’s US$4-trillion hoard of treasuries, most of which is in the belly of the yield curve or at the long end, says Jack Ablin, executive vice president and CIO with BMO Harris Private Bank, a division of Bank of Montreal, in Chicago.

“Selling mid- to long bonds would drive down bond prices, bring up yields and make for a flatter yield curve if the short end rises along with the belly,” Ablin says.

A flat or flatter yield curve narrows the term premium – the extra yield that investors expect for taking on 20 or 30 years of risk in comparison to five or 10 years. This is normal when economic growth is healthy. But, Ablin warns, if central banks make a miscalculation, the yield curve could become inverted, with long rates falling below short rates. An inverted yield curve can signal a coming recession, he adds: “Every recession has been preceded by an inversion.”

Taking the consensus view that the Fed will raise rates in 2015, the process will begin with a lift of the overnight rate from 0.25% to 0.50% in the second quarter, followed by other lifts to 1% at the end of 2015. The rise in short rates would push up other rates.

In Canada, BoC governor Stephen Poloz has hinted that rates will hold at 1% well into 2015. On Dec. 3, he announced that the BoC would hold its overnight rate at 1% in spite of what the bank called “signs of a broadening recovery.”

Parsing Poloz’s words, economists took this statement to mean that there could be a case for higher rates later this year unless there’s a severe downdraft caused by collapsing energy prices and related energy equities prices. Yet, Poloz’s words had little impact. Short rates were unchanged and long rates dropped in the mid-December rush to safety as stocks dived during the correction to energy prices.

What to do?

The recovery path suggests shortening terms and picking up yield on investment-grade corporates. But there are other strategies, depending upon your view of economic prospects and the deflation risk, says Chris Kresic, senior partner and head of fixed-income with Jarislowsky Fraser Ltd. in Toronto.

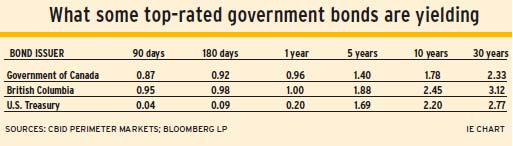

If you think sluggish global growth will prevent a rise in short- and medium-term rates, with long rates in particular not changing much, you could use a “bullet” strategy: pick one maturity date for all your clients’ bonds, but purchase them at different times. Kresic suggests targeting the FTSE/TMX index average duration of 7.4 years with an average term of 8.5 years. Your yield to maturity would be 1.8%.

If, on the other hand, you think rates will decline – a view consistent with deflation and major economic weakness – you could use a “barbell” strategy: select a couple of maturity dates, one short and the other long. The shorts would be reinvested when they mature while the longs would gain value with falling rates. To achieve index-type duration, assuming 20-year duration on the 30-year government bond, you’d have 30% in long bonds and 80% in two-year bonds. The average yield would be 1.45% in this Government of Canada bond portfolio.

There is no easy answer to the continuing recovery/faltering growth conundrum, Kresic says: “You have to take a view. Ours assumes that it is more likely for long rates to go down than up. The 30-year bond’s yield to maturity could drop by as much as 50 basis points, we think. Our concern is that the BoC will apply contractionary measures before the economy is ready for them.”

As a result, Kresic favours the bullet approach, a worst-case scenario strategy that trims losses for clients if rates rise and would produce handsome returns if long rates decline.

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.