The financial advisors surveyed for this year’s Dealers’ Report Card are taking home less in pay than last year as a result of a decrease in client assets under management (AUM) and changes to the compensation structure at some firms.

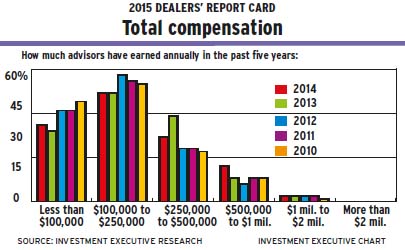

Specifically, the average book of business for advisors has dropped to $34.4 million from $36.5 million year-over-year. This decline in AUM appears to have resulted in a decline in advisors’ annual compensation, with the percentage of advisors who earned less than $250,000 a year rising to 62.9% from 60.6% last year while those making more than $250,000 a year has dropped to 37% from 39.4% year-over-year.

Still, despite this dip in pay, the overall average performance rating for the “firm’s total compensation” category remained the same as last year, at 8.3. However, closer inspection reveals that certain changes to some firms’ payout structures led to dissatisfaction among some advisors – and many of them blame these changes for the decrease in their pay.

For example, advisors with Lévis, Que.-based Desjardins Financial Security Independent Network gave their firm the lowest rating of any dealer in the compensation category – at 7.4, down from 7.8 last year – because some Desjardins advisors took a hefty pay cut when the firm recently altered its payout grid.

“My annual salary got chopped to $70,000 from $82,000. Our compensation used to be higher and our new business model has changed things drastically,” says a Desjardins advisor in Ontario.

Adds a colleague on the Prairies: “The firm used to take 50% [of my annual revenue], and now it takes almost 80%.”

The reason for the change is that Desjardins has four networks of advisors and, in 2014, the firm harmonized the processes of two of those networks – DFSI Legacy Performa and DFSI Legacy MGI. As a result, the 100 or so advisors with the DFSI Legacy Performa network saw an impact on their fees and the grid, says Nancy Schafer, Desjardins’ regional vice president, sales and distribution, for Western Canada. She notes that in return for the lower payouts, “these same advisors now have access to new tools and services that did not exist in that network before.”

Toronto-based HollisWealth Inc. also made changes to its compensation structure, primarily affecting advisors at the lower end of that firm’s grid.

“They’re increasing the minimum threshold and adding fee increases, which makes it difficult for advisors with smaller clients who have assets of less than $100,000,” says a HollisWealth advisor in Ontario. “It’s getting expensive to be connected to this firm.”

Adds a colleague in British Columbia: “Compared with the rest of the industry, the compensation here is still good; but the most recent change hasn’t made me happy. On Jan. 1, they cut the compensation for everyone of less than $250,000 [in annual revenue]. They said it was to enhance our performance, which I don’t get.”

Although the firm has a policy not to disclose how its grid has changed, Tuula Jalasjaa, managing director and head of the retail advisory network at HollisWealth, says the “hurdle rates” were changed to create a competitive compensation plan: “We didn’t believe our [previous compensation packages],” she says, “incented growth at some levels.”

In an attempt to ease the transition, HollisWealth gave its advisors a one-year window to reach those hurdles, Jalasjaa adds: “If [advisors] did focus on [achieving] some growth, then [the new model] would have a negligible or very small impact on them. We wanted to give advisors that opportunity and give them all of the resources and support that they could leverage to help them grow during that period.”

In contrast, the firms that kept their compensation structures stable fared better among advisors, who gave these dealers much better marks.

“Some firms reduce the grid, but fail to recognize that the grid is a percentage. If revenue goes up or down, it affects the firm and the advisor. Manulife hasn’t [cut its grid],” says an advisor in Atlantic Canada with Oakville, Ont.-based Manulife Securities, the compensation for which was rated at 8.7.

An advisor in Ontario with Montreal-based Peak Financial Group, which was rated at 8.6 in compensation, says, “Through the good times and the bad, Peak would rather make changes to central operational costs rather than download those costs on to the advisors.”

Some advisors are so thankful for stability in their compensation model that this may have resulted in increased ratings for some firms. For example, Richmond Hill, Ont.-based Global Maxfin Investments Inc., which was tied with other firms for the overall lowest compensation rating of 7.8 in the past two years, saw its rating rise to 8.4 this year – the largest gain among any firm in the compensation category.

“They offer 100% payout. I just pay a desk fee and take what I earn. It’s the best in the business,” says a Global Maxfin advisor in Alberta.

Global Maxfin, which acquired Calgary-based Professional Investment Services (Canada) Inc. (PIS) in late 2009, allowed the advisors who joined Global Maxfin as a result of that deal to keep their previous firm’s flat-fee model. It’s important to note, though, that Global Maxfin advisors who joined the firm in other ways than that acquisition are on a grid structure.

What’s interesting is that Global Maxfin hasn’t made any recent changes to its compensation package, according to Bruce Day, the firm’s president, yet the firm saw its rating increase substantially this year. Day posits that the former PIS advisors now recognize how competitive their compensation structure is, given all the significant changes that have taken place in the industry.

Maintaining a stable, consistent and fair payout also is the reason why advisors with Windsor, Ont.-based Sterling Mutuals Inc. said their firm’s compensation is the best in the business, rating it a survey-high of 9.2, up from 8.8 in 2014.

“They pay very well,” says a Sterling Mutuals advisor in B.C. “It’s an 80/20 split, and then they have a ceiling; once I hit that, the payout is 100%.”

© 2015 Investment Executive. All rights reserved.