This article appears in the 2023 ETF Guide issue of Investment Executive. Subscribe to the print edition, read the digital edition or read the articles online.

Financial market performance in the first half of 2023 could hardly be more different from the previous year’s crushing declines, but ETF investors have largely stuck to their 2022 playbooks. Defensive fund categories that topped sales last year are repeating their success.

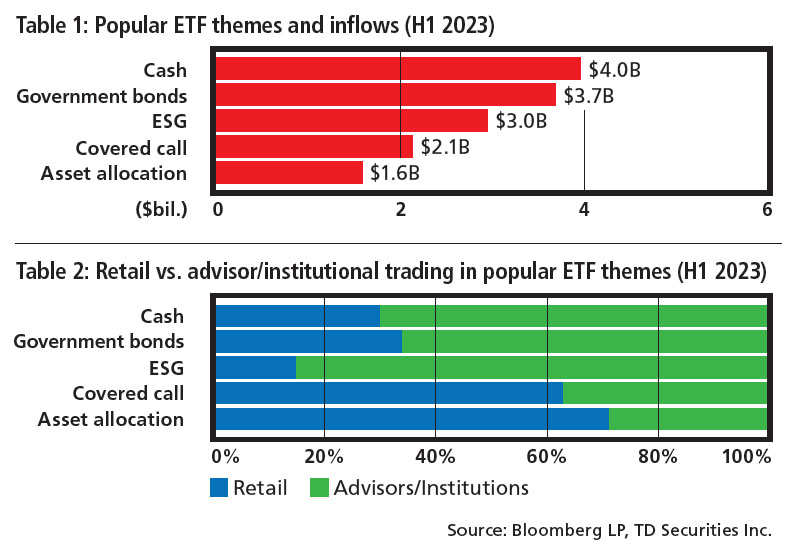

Once again, cash beat all challengers, bringing in $4 billion as of June 30, according to TD Securities Inc. Covered calls maintained their momentum, with several new products launched and $2.1 billion in inflows, while government bonds were popular as investors prepared for a long-prophesied recession. (See Table 1.)

But who’s buying these themes? Knowing for sure is difficult but trading patterns provide clues, said Andres Rincon, director and head of ETF sales and strategy with TD Securities. For starters, Rincon assumes block trades, commonly defined as more than 10,000 units, are institutional. Same for cross trades, which are executed dealer to dealer and therefore rule out an individual retail investor.

“After a certain size, it’s generally an indication that it’s being done by a dealer on behalf of a larger client, which is [financial] advisors or institutional clients,” Rincon said. “So, if you’re looking at who’s really executing a trade in general, you can look at what’s being done on a block or a cross versus what’s being done on the board.”

As for distinguishing between institutions and advisors, Rincon uses observations from the trading desk to inform his assumptions.

Quest for cash and yield

While assuming do-it-yourself (DIY) investors are loading up on high-interest savings account ETFs may be logical, Rincon said, the trend is attributable mostly to advisors. One reason may be that several banks have blocked the sale of these ETFs to retail investors through bank channels. “That’s the only reason it’s so skewed,” he said.

Rincon said more than two-thirds of the cash ETF trading value was crossed and large, but he attributed the buying to advisors rather than institutions. “Because it’s cash, and the entire world is cash-heavy right now, these trades tend to be large,” he said.

With covered calls, the nature of the trading is the other way around. Despite the products’ complexity, Rincon said, DIY investors are doing most of the buying. However, he noted, this is a recent phenomenon. The category used to be advisor-heavy, but that began to change during the Covid-19 pandemic, when interest rates dropped to near zero and investors became more adventurous in their search for yield.

That approach has persisted, even with interest rates topping 5%. Of the $2.1 billion that has flowed into covered-call ETFs this year, Rincon said, more than 60% is from individual investors.

“Canadian investors are very yield-centric,” he said. “They want yield more than they want growth. Because of that need for yield, you’re going to get a huge move to covered calls.”

As a result, covered calls account for about 5% of total ETF assets in Canada, Rincon said, compared with only about 0.5% in the U.S. market.

Click image for full-size chart