Research by:

Sangjun (John) Han, Roland Inacay, Tiana Kirton, Diane Lalonde, Ciara Lalor-Lindo, Alisha Mughal and Sai Tamanna Sharma

Research editor:

Katie Keir

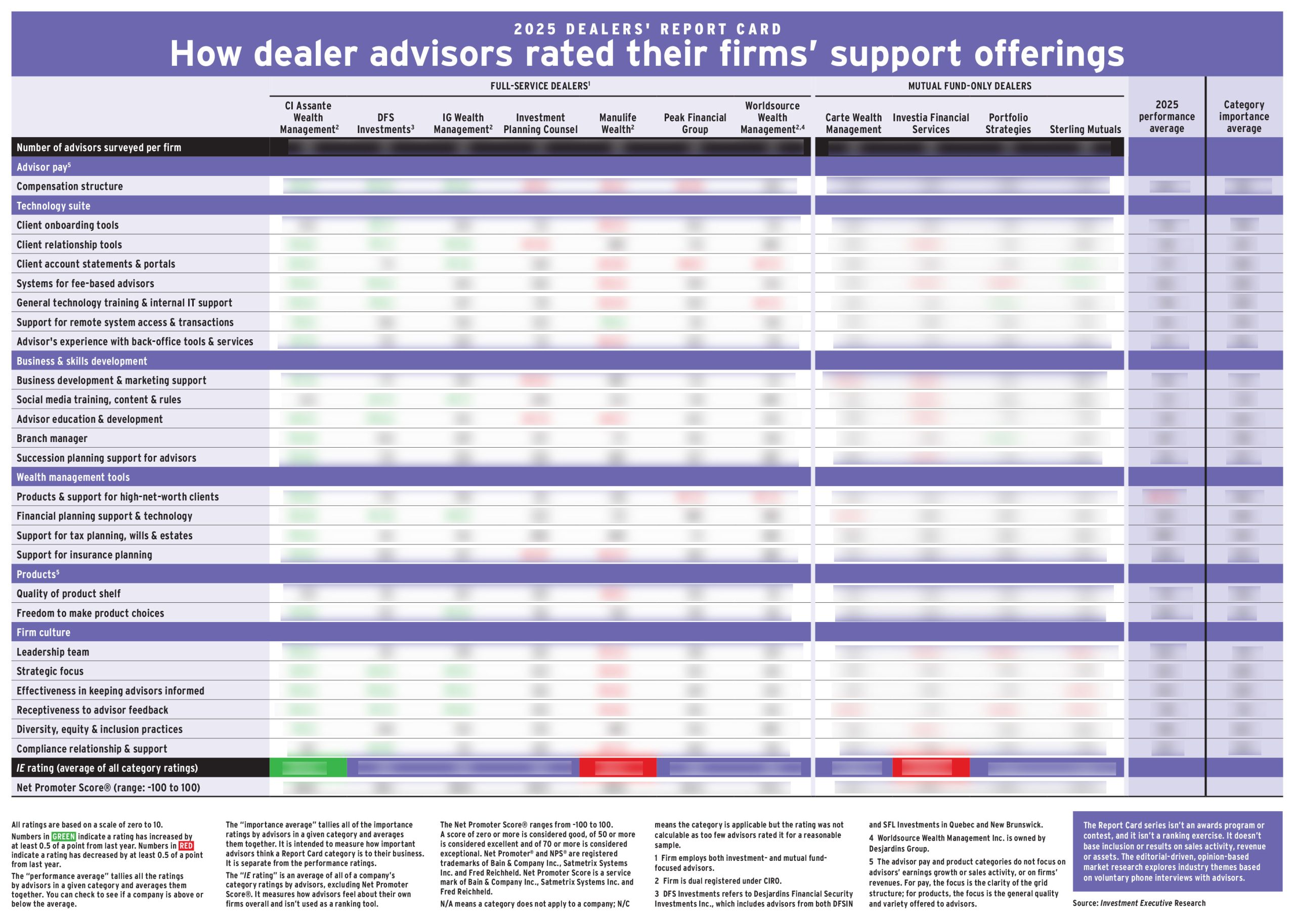

Click the image of the main data table below to obtain a PDF of the results table (scroll past the ad if you see one, to the table image that follows). The form requires an email address.

This article appears in the September 2025 issue of Investment Executive. Subscribe to the print edition, read the digital edition or read the articles online.